| | By David Whitley

Special to ESPN.com

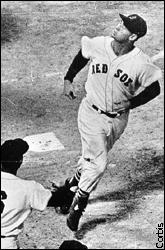

Ted Williams wanted to be known as the greatest hitter who ever lived. When he failed to meet those expectations, pity anything that got in his way.

Like a water cooler. After popping up in a minor-league game, he was so angry that he came back to the dugout and put his fist through a glass cooler. "It just exploded," Williams said. "Blood's flying, glass, everything. I was lucky I didn't cut my hand off.

If he had, there would have been no Teddy Ballgame. No .406 average. No Terrible Ted.

|  | | Williams had a lifetime batting average of .344. |

Who is baseball's greatest hitter? That debate will never have a clear winner. But Williams probably produced more hits, more admiration and more mixed feelings from his own hometown fans than anyone who ever played.

The Boston Red Sox leftfielder belted 521 homers, batted .344 and had 1,839 RBI. He won two Triple Crowns. His .483 on-base percentage is baseball's best, with Babe Ruth second at .474. In slugging percentage, Williams' .634 trails only Ruth's .690. Williams' .406 average in 1941 is one of sport's magic numbers. No player has topped .400 since.

The Splendid Splinter dominated the 1940s. In his seven seasons that decade, he led the league in runs batted in three times, batting and home runs four times each and runs six times.

|  | | Williams flew combat missions for the Marines in the Korean War. |

As good as Williams was, people will always wonder what might have been. What if injuries had not cost him almost two full seasons? What if five of his prime years had not been spent in the Navy in World War II (1943-45) and flying combat missions for the Marines in the Korean War (most of the 1952 and 1953 seasons)?

And what if he had been as determined to be liked as he was determined to be a great hitter? Williams flew a career-long combat mission with fans and the press. "I'm the guy they love to hate," he said.

His charitable work for children made him an institution in New England. He might not have cared about being loved, but Williams definitely didn't like being hated.

"When somebody says nice things about me, it goes in one ear and out the other,"' he said. "But I remember the criticism the longest. I hate criticism.'"

He won two MVPs, but might have won twice that many if he hadn't alienated the writers who voted for the award. For all the things he did, many remember Williams for what he refused to do - tip his hat to the fans at Fenway Park.

They booed him early in his career, and Williams never forgave them. The criticism may have bothered him, but it also may have fueled the fire that made Williams such a respected batter.

He was born on Aug. 30, 1918, in San Diego. Growing up, he was shy and sensitive. "I was awfully self-conscious as a kid - about everything,"' he said. "The way I looked and things I didn't have that some of the other kids did."

His mother worked long hours as a Salvation Army worker, so Williams spent much of his time on playgrounds, developing a skill that few have ever been able to match. "I used to hit tennis balls, old baseballs, balls made of rags - anything," he said. "I didn't think I'd be a particularly good hitter. I just liked to do it."

He was wrong. All that left-handed hitting got him noticed by a scout. After graduating high school, Williams signed with the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League. Two seasons later, the Red Sox bought his contract for $25,000 and four players.

He spent one season with Triple-A Minneapolis before breaking in as Boston's 20-year-old rightfielder in 1939, hitting .327 with 31 homers.

Williams tipped his hat for every home run that season. He was embraced as "The Kid," and Boston had visions of a man who one day might break Babe Ruth's home-run record.

The Red Sox moved the rightfield fence in following Williams' rookie season. Wanting to protect his keen batting eye, he moved to leftfield so he wouldn't have stare into the sun. Williams slumped to 23 homer in 1940.

He still batted .344, but that wasn't enough to erase the frustration. Part of it was Williams' look. He was a gangly 6-foot-3 and 205 pounds, and his long legs made it appear he was loping and never running as hard as he really was.

One game he struck out, then made an error. He heard the boos, and he couldn't get the echo out of his head. "In the dugout between innings, I swore never again to tip my hat in Fenway Park,"' he said.

It was the start of a not-so-beautiful relationship between Williams and "those wolves in the leftfield stands."' His dealings with the press weren't any better.

|  | | Williams spits into the air as he crosses the plate after hitting his 400th homer. |

"If his noodle swells another inch, Master Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox won't be able to get his hat on with a shoehorn," wrote Jack Miley in the New York Post. "For when it comes to arrogant, ungrateful athletes, this one leads the league."

Williams routinely led the league in critics and hitting. On the final day of the 1941 season, he had a .39955 batting average. It would have been rounded up to an even .400 if he'd chosen not to take another at-bat. But Williams was never one to back down from any challenge, and played in both games of the doubleheader.

He went 6-for-8. It was the finishing touch on an astounding accomplishment, yet Williams lost the MVP award to Joe DiMaggio, who had his 56-game hitting streak that season.

There is no telling what kind of damage Williams might have done to pitchers if he hadn't been serving in the military in two wars? It's not unreasonable to think he could have passed Ruth's 714 homers.

Was he the greatest hitter ever? Others have hit for higher averages, had more home runs, more RBI. Williams would have been near the top of every career category if military service hadn't intervened. And a more confident man never entered the batter's box.

"Some call it courage," he said. "I call it confidence in yourself. Knowing you can hit any pitcher alive."

Few ever played so well for so long. He batted .388 in 1957, and won the A.L. batting title again at .328 the following season at age 40. His eyesight and discipline at the plate were legendary. In 7,706 at-bats, Williams struck out only 709 times.

Whatever he did, there was the love-hate relationship with Boston fans. "Williams is a peculiar case, so tangled in his inner man that even a psychologist or psychiatrist would have trouble unraveling him," wrote Arthur Daley in The New York Times. "He is more hated than liked by those who know him best."

But on the final day of the final homestand of the 1960 season, 10,454 fans showed up at Fenway to give a loving goodbye to the 42-year-old Williams.

Boston's mayor presented a $1,000 check to the Jimmy Fund, the children's charity Williams championed. The local sports committee presented a plaque. The inscription wasn't read in its entirety, since Williams hated to be fussed over. He then took the microphone.

"I want to say that my years in Boston have been the greatest of my life," Williams said.

When he came to bat in the eighth inning, Fenway erupted. Everybody wanted a dream ending, and Williams provided it. He hit a home run, and ran the bases like he'd done 520 times before - head down and fast. After touching home plate, he went straight to the dugout.

"We want Ted!" the crowd yelled.

He never came back out. As author John Updike wrote, "Gods don't answer letters."

Williams managed the Washington Senators and Texas Rangers from 1969-72, compiling a 273-364 record. After his retirement, Williams spent much of time fishing, and was as proficient with a rod and reel as he was with a bat.

| |

ALSO SEE

Ballgame Notes

Quotes

|