| | Sixty-three years.

Moses Fleetwood Walker played his last major league game in 1884.

Jack Roosevelt Robinson played his first major league game in 1947.

Between those two, not a single man of known African heritage played in a major league game. Not in the American League or the National League, nor the Players League or the American Association or the Federal League.

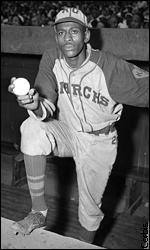

|  | | Satchel Paige was a star pitcher for the Kansas City Monarchs in the 1930s. |

One of the appealing things about sports is that, for the most part, they are merit-based. Hit .300, move to the next level. Win 20 games, consider yourself promoted. But for 63 years, it didn't necessarily matter how good a hitter hit or a pitcher pitched; if one of his parents or grandparents or great-grandparents was black and anyone knew about it, he wasn't moving to the highest level.

Those three score and three years constitute a dark period -- or should that be "a white period"? -- in baseball's history, a period in which a man's skin color counted for as much as his ability to hit or field or throw.

Thus, fans of American League and National League teams missed seeing some of the greatest baseball talent this planet has produced. And in the minds of many historians, the "greatest of the greatest" were pitcher Satchel Paige and catcher Josh Gibson.

How good was Paige? Consider that he didn't reach the American League until 1948, just short of his 42nd birthday. His first season, he started only seven games, but tossed shutouts in two of them. He also posted a 2.48 ERA. In his five seasons as a major leaguer, Paige compiled a 3.29 ERA, roughly 25 percent better than the league average over the same span. There seems little doubt that if he'd been in the major leagues and healthy during the 1930s and '40s, he would have rivaled men like Lefty Grove, Carl Hubbell and Dizzy Dean as baseball's greatest pitcher.

Paige had great speed and great control, plus all the other things that make a great pitcher great. Imagine Pedro Martinez, just as skinny but four inches taller, and you start to get the idea. But of course, Satchel Paige was more than just a pitcher, he was also a showman, the P.T. Barnum of the baseball world. Every day with Paige was a parade and a circus and a party all rolled into one. While he pitched for eight different Negro League teams -- for whom he won 124 games and lost 80 -- he also spent many months barnstorming, pitching three innings at a time for adoring crowds all over the country.

How good was Josh Gibson? Records of his performances remain hazy, but it's quite possible that he had more power than anyone who ever played the game, at least until Mark McGwire came along. Gibson played many of his Negro League games in Washington's spacious Griffith Stadium. In its history, the back wall of the left-field bleachers was cleared only three times: once by Mickey Mantle and twice by Gibson. He also hit for average, and the latest edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia has him batting a career .362 in 501 official Negro National League games.

Gibson was diagnosed with a brain tumor early in 1943. He refused surgery, and died of a stroke early in 1947, just a few months before Jackie Robinson debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Gibson was only 35, and might eventually have followed Robinson to the major leagues if not for his early demise.

How much was lost when Organized Baseball, in its nonexistent wisdom, refused entry to incredibly talented men like Paige and Gibson?

Before we answer that, a story; the story of a wise Chinese farmer whose horse ran off. When his neighbor came to console him, the farmer said, "Who knows what's good or bad?"

The next day, the farmer's horse returned, and behind her was an entire herd of horses. The foolish neighbor came to congratulate the farmer, who replied, "Who knows what's good or bad?"

The next day, the farmer's son broke his leg while trying to ride one of the horses, and the foolish neighbor came to console the farmer yet again. "Who knows what's good or bad?" replied the farmer.

The next day, the army passed through, looking for able-bodied men. But because the farmer's son had a broken leg, he was spared from conscription. Once again, the foolish neighbor came to congratulate the farmer. And once again, he replied, "Who knows what's good or bad?"

Segregation and baseball's color barrier were disgusting, reprehensible, and everything in between. But you know, a fair amount of good came out of Satchel Paige's long absence from the lily-white major leagues. He wound up pitching in those same major leagues until he was 47 years old. Would that have happened if he'd thrown 250 innings per season while in his early 20s? Or would he, like his spiritual kin Dizzy Dean, have been washed up when he was only 27 years old?

Remember, too, that Paige did pretty well for himself financially. By the late 1930s, he was making around $40,000 per annum, most of that money coming from side deals on his barnstorming trips. By comparison, in 1940 Bob Feller drew a $50,000 salary from the Cleveland Indians. But Paige's career as a professional baseball pitcher lasted roughly 32 years, or about twice as long as Feller's. In fact, it's not unreasonable to posit that Paige made more money throwing a baseball than anyone, black or white, until at least the 1960s.

What's more, the barnstorming antics that made him famous -- summoning his outfielders from the field of play, then striking out the side was one of Paige's favorites -- would never have happened in the big leagues. Had Satchel Paige spent his career in Organized Baseball, he might be just another Hall of Fame pitcher, rather than a true legend.

And what of Gibson? Did the color barrier lead to his untimely end? Was his descent into illness, some of it related to substance abuse and some not, hastened by Organized Baseball's institutionalized segregation? Gibson's son, Josh Jr., will have none of it. As he told author Mark Ribowsky, "When I hear all that stuff about how my father died of a broken heart, that [pisses me off]. 'Cause that wasn't my father. He was the last guy to brood about something he couldn't do nothin' about."

And what of the black baseball fans? For roughly three decades, they had their own great baseball teams -- the Kansas City Monarchs and the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords, to name just a few -- for which to cheer. While it's true that baseball fans of all colors are now welcomed into every baseball stadium across the land, it's also true that the great majority of faces one sees in those baseball stadiums are not very colorful.

Then there are all the white baseball fans who saw some of the game's greatest players, fans who lived in towns and small cities all around the country, fans who never saw a "real" major leaguer until they owned a television. To this day, you can bet there are still old men in North Dakota who reminisce about "the day Satchel Paige came to town."

No, the tragedy was not to the game, or the fans. Neither really knew what they were missing. The only real injustice was done to the players themselves, because they were not allowed to go as far as their talents might take them.

Rob Neyer is a staff writer for ESPN.com.

| |

ALSO SEE

ESPN.com's 10 unfortunate events

Message Board

|