| | By David Schoenfield

ESPN.com

Look at the following career statistical lines for two players, now retired,

who made their major-league debuts in the 1980s:

Player A

|

Yrs.

|

Gms.

|

Hits

|

Runs

|

2B

|

3B

|

HR

|

RBI

|

BB

|

SO

|

Avg.

|

OBP

|

SLG

|

|

14

|

1785

|

2153

|

1007

|

442

|

20

|

222

|

1099

|

588

|

444

|

.307

|

.363

|

.471

|

Player B

|

Yrs.

|

Gms.

|

Hits

|

Runs

|

2B

|

3B

|

HR

|

RBI

|

BB

|

SO

|

Avg.

|

OBP

|

SLG

|

|

14

|

1747

|

1749

|

903

|

312

|

18

|

293

|

1086

|

838

|

798

|

.282

|

.370

|

.481

|

Pretty similar, aren't they?

Both happened to be left-handed-hitting first

basemen. Player A finished with a few more hits and a higher batting

average, but Player B, by virtue of his advantage in power and walks, had a

slightly superior on-base percentage and slugging percentage.

Player A won an MVP Award and made six All-Star teams. On the other hand,

his team never won a postseason series while Player B was a key performer on

two World Series champions.

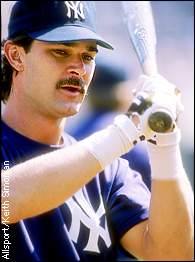

Player A is Don Mattingly, who becomes eligible for the Hall of Fame for the

first time this winter and will presumably draw a fair amount of support from the voters. Player B is Kent Hrbek. He was on the ballot last winter, received just five votes and was dropped from future

consideration.

|  | | Don Mattingly is on the Hall of Fame ballot for the Class of 2001. |

The Mattingly-Hrbek comparison is a good illustration of why baseball's Hall

of Fame debates rage on a little more intensely than other sports. Mattingly

was famous and had a high level of peak performance, but over the course of

his entire career had essentially the same value as Hrbek. But while we know Hrbek isn't a Hall of Famer, it isn't so easy to write off Mattingly.

The comparison is important to note because while Don Mattingly may appear like a player with Hall of Fame credentials, it must be remembered that career length is a vital consideration for baseball's Hall of Fame

voters.

In basketball or football, a short burst of excellence may be worthy

of Hall of Fame standards. But in baseball, a five- or six-year run of

All-Star play usually isn't going to cut it. For example, Tony Perez

just made it over the likes of Dale Murphy and Jim Rice. Murphy won two MVPs

and Rice won one. Perez, who never came close to being an MVP, lasted longer, thus finishing with some higher career totals.

That's how de facto standards often come into play -- 300 wins,

3,000 hits and 500 home runs are all virtual tickets to Cooperstown. You don't have that in the NBA -- how many career points "ensures" Hall of Fame selection? Who knows. Yet in baseball, reaching these standards means automatic enshrinement.

That brings up two issues:

The standards are starting to change. All the home runs today mean the

number of players with 400 and 500 career homers will increase dramatically

in coming years. Jose Canseco may reach 500 home runs, but was he a great

player? There are only two active pitchers who currently have a clear shot

at 300 wins -- Roger Clemens and Greg Maddux. Does that mean no other

pitchers are Hall-worthy? Heck, Harold Baines has a shot at 3,000 hits. Is

he a Hall of Famer?

And perhaps more importantly, the Hall of Fame isn't about players like Tom

Seaver and Mike Schmidt -- guys who put up the kind of numbers that make them first-ballot locks. There are many more like Perez, Jim Bunning, Orlando Cepeda and Bobby Doerr -- players who don't hit the magical mark, but nonetheless eventually get elected.

Baseball's Hall of Fame debates are somewhat created thanks to a two-tiered voting system -- two groups with widely different standards. First, after five years of retirement, a player appears on the Baseball

Writers ballot. If he gets 75 percent of the vote, he's in. Of course,

writers will change their votes from year to year, which explains why Perez doesn't make it when George Brett and Nolan Ryan are on the ballot, but squeaks in when it's a weak class. Most think the writers, in general, do a pretty

good job with this process, with Perez the "weakest" player they've elected in many years.

If a player isn't deemed worthy by the writers -- he gets 15 years on the

ballot -- then the 15-member Veterans Committee can vote him in. Having a

few buddies or ex-teammates on the panel will help a player's cause. The Veterans

Committee, which includes players, writers and executives, is also

responsible for adding umpires, managers, executives and Negro Leaguers.

In fact, the Veterans Committee has pulled some whoppers during its time. In

the late '60s and early '70s, Frankie Frisch was an influential member of

the panel. He was a Hall of Famer with the New York Giants and St. Louis

Cardinals in the 1920s and 1930s, and the committee elected a bunch of his

pals from those teams -- George Kelly, Jim Bottomley, Jesse Haines, Dave

Bancroft, Chick Hafey, Fred Lindstrom. Those guys are all among the worst players in the Hall of Fame.

Another thing worth noting -- since voters place an important emphasis on career value, single-season or postseason heroics are not usually a deciding factor for election. Roger Maris never made it the Hall of Fame, despite his 61-homer season. Kirk Gibson hit some dramatic World Series home runs, but those won't be enough to get him elected.

Which leads us back to Hrbek and Mattingly: Similar numbers, similar careers. One's already out. Will the other make it?

The debate rages on.

David Schoenfield is the baseball editor at ESPN.com. | |

ALSO SEE

Garber: What is a Hall of Famer?

Basketball: Open to all

Football: Fame is name of game

Hockey: Will offensive cycles give Hall headache?

In-depth: The Hall of Fame debate

|