In a four-part series, ESPN.com explores the impact of baseball on the political career of Republican presidential candidate George W. Bush. Part one focuses on his management style.

ARLINGTON, Texas -- It wasn't that many years ago that George W. Bush was sitting right down there in the field boxes near the on-deck circle and was sending the batboy into the dugout for a handful of sunflower seeds. Now, he's within a week and a national election of being the man who may summon the Secretary of Defense to the Oval Office and deploy American troops around the world.

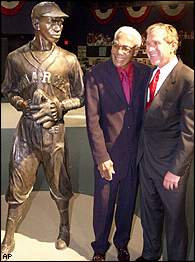

|  | | Bush, campaigning in September, chatted up Hall of Famer John "Buck" O'Neil during a tour of the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo. |

Then managing general partner of the Texas Rangers, Bush would kick his cowboy boots up on the railing, spit out the husks of the sunflower seeds and shoot the bull under starlit summer skies with his guest of the night, sometimes a Rush Limbaugh or a Muhammad Ali, other times his wife and daughters or some local corporate honcho.

He would be there for almost every home game, usually until the last out, yelling encouragement to a Julio Franco at the plate, exchanging howdys with fellow Texans who wandered down the aisle to shake his hand, signing his own special baseball card for the kids and their charmed parents, too.

Sounds like a great job, maybe even the most-fun job on earth, but is this any way to train for the big job, the one his father once held?

"Bush didn't handle the financial side (of the Rangers)," says Evan Smith, editor of Texas Monthly magazine. "But it was Bush who dealt with the public. Bush who raised money. Bush who made the hard decisions, and Bush who delivered the bad news. Guess what? That's what a president does."

"He can quote baseball stats better than anyone I know," says Molly Beth Malcolm, chair of the Texas Democratic Party and a former Republican. "But, my goodness, this is an election for the leader of the free world."

|

You can take the boy out of baseball

|

|

AUSTIN, Texas -- In some respects, it's hard to tell that George W. Bush ever left baseball.

A bat inscribed "Best of Luck in 2000. Your friend, Mark McGwire" lies in a case next to his desk in the Capitol statehouse. Nearly 250 autographed baseballs -- Stan Musial, Sandy Koufax, Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams, some going back to Bush's childhood -- sit in wooden cases that dominate the first wall a visitor sees when entering the governor's office. There are fewer books than baseballs.

On the campaign trail, Bush's aides carry his suits in a Rangers garment bag and his workout clothes in a Rangers gym bag. During the primaries, when asked his greatest regret, he said trading Sammy Sosa to the Chicago White Sox. He still calls Nolan Ryan his hero and last year he attended Ryan's Hall of Fame induction. A feature for kids on his Web site explains that "running for president is a lot like playing baseball."

At 30,000 feet, Bush works the back of his campaign jet like he once walked the Rangers' press box, bantering with journalists he calls by their first names or, sometimes, sports-themed nicknames.

While the reporters might have trouble getting him to talk casually about the details of his positions on key voter issues, during the baseball season he commiserated with one reporter, a Boston fan, after a drubbing of the Red Sox. Another time he went on about the Rangers' prospects in the American League West, and threw out a trivia question: Name an all-star team of players who won two straight MVP awards. The reporters came up with three-fourths of the team. Bush gave them the rest.

The ex-team owner is obviously still on his game.

|

Somewhere in there is the truth, and on Nov. 7 the voters will decide whether being in charge of the Texas Rangers is a valid line for the resumé of a president of the United States. If they say, "yes, it is," what would George W. Bush's years with a baseball team tell us about his years in the White House?

They would tell us a lot about how he operates.

The Bush camp has never suggested that negotiating a stadium deal is tantamount to negotiating a missile defense treaty, but aides will not allow his time with the Rangers to be dismissed as irrelevant. They argue that running a high-profile baseball team and working with a multitude of constituencies helped prepare Bush for elective office, first in 1994 as governor of Texas and now as president.

Before joining the Rangers in 1989 and launching his public career, Bush ran several oil exploration companies -- Arbusto (1977-81), Bush Exploration (1981-84) and Spectrum 7 (1984-86) -- none as large, complex or visible as the Rangers. None as successful, either, each eventually being absorbed by a larger competitor at a time that low oil prices caused many small independents to struggle.

"Bush has experience as a chief executive," says Dan Bartlett, spokesman for the Bush-Cheney 2000 campaign. "He had to meet payroll and deal with the nature of the business cycle. He understood there were a lot of families that counted on his leadership and stewardship of a team."

Former colleagues describe a chief executive who took the role of figurehead for the ownership group, created policy and set budget, then left the execution to team president J. Thomas Schieffer. Bush's co-general partner, Rusty Rose, ran the financial side.

Bush managed by walking the office and visiting with employees in informal, one-on-one settings. He cared more about the big picture than the small details. He preferred specific recommendations to a series of options. Reprising his prep school days at Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., he was more head cheerleader than executive director.

He almost always delegated responsibility and almost never questioned the decisions of those he empowered. While he clearly had opinions about players, he wasn't "one of those ridiculous, socks-and-jocks owners" who wants to make trades and design the uniforms, says Tom Grieve, the Rangers' general manager during 1984-94.

Bush was blindly competitive, sometimes over trivialities. Like the time Grieve invited his new boss over to watch a game and Bush opened the refrigerator without asking, as if he had grown up there, and started eating from a plate of large chocolate and whipped cream cookies Grieve's wife had made.

"What's the family record?" Bush asked. "Three," Grieve said. So, Bush ate a couple more.

Unlike the stereotypical dictatorial team owner, Bush had to work with others to get things done. Like a governor working with the legislature or the president with Congress, Bush was proficient at building consensus among the club's 29 limited partners. He held only 1.8 percent of the Rangers and the ownership structure required that every major decision gain the consent of Rose, who praises Bush's interpersonal skills in avoiding clashes.

Bush's down-to-earth style endeared him to the staff. He insisted on wearing shoes so traveled that they had holes in the soles. Rose says when he bought Bush a pair of Gucci loafers "he thanked me, then returned them to Neiman Marcus and got cash."

Bush valued tradition and loyalty.

At Major League Baseball meetings, he fought lonely, losing battles against an expanded playoffs and interleague play, arguing that one of baseball's greatest strengths is a fan's ability to reasonably compare the Mark McGwires of today with the Babe Ruths of yesteryear. And, in 1992 he gave an impassioned, losing plea to keep Fay Vincent, a family friend who spent a summer with the Bushes in West Texas when George W. was a boy, on as commissioner.

Yet, Bush "never made any enemies," says Chicago White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, who led the coup that deposed Vincent. "Everyone liked George."

George Will, the syndicated columnist and baseball author, cites that attribute in terming Bush presidential timber. "Anyone who has been in a room with those 30 owners will find dealing with the Arab-Israeli dispute a piece of cake," Will says.

President Bill Clinton took an opposing view in July: "The message of the Bush campaign is just that, I mean, 'How bad could I be? I've been governor of Texas. My daddy was president. I owned a baseball team' "

Some in baseball were impressed enough with Bush's manner and management style that in 1993 he was mentioned in the media as a possible replacement for Vincent.

Schieffer says that it was "more than just casual talk" and that Bush truly wanted the position, while Bud Selig, then interim and now permanent commissioner, is coy about how seriously Bush was considered. Selig says discussions never reached the formal stage.

At the time, the owners were content to go with an interim commissioner of baseball during the '94 labor dispute, retaining direct control themselves, Will says. Tired of waiting for baseball to give him a sign, Schieffer says, Bush entered the governor's race later in the year.

Jim Reeves, who covered the Rangers at that time for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, says: "I don't recall Bush-for-commissioner as being serious at all. At least we didn't take it very seriously around Dallas-Fort Worth, and I don't think baseball ever did."

Soon, it will be up to the voters to decide if they take George W. Bush's pitch seriously.

Tom Farrey is a Senior Writer with ESPN.com. He can be reached at tom.farrey@espn.com. Read part two of his series on Thursday.

|

ALSO SEE

Slideshow: Photos that defined a candidate

Timeline: George W. Bush and Rangers

Bush family links to sports go back a century

Politicians who rubbed up against sports

Gore can play that game, too

|