| |

|

|

| Tuesday, February 18 Updated: November 14, 3:30 PM ET Flexing a team's offense By Fran Fraschilla Special to ESPN.com |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At some point during the college basketball season, you will hear the announcers use the term, "The Flex Offense."

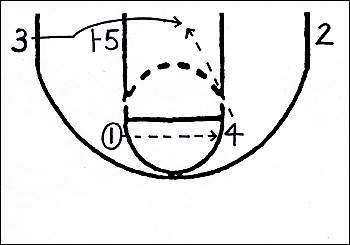

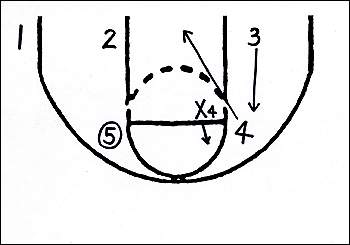

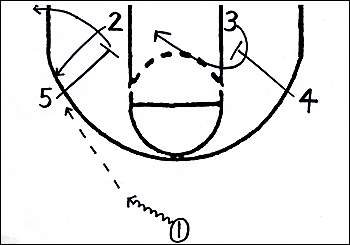

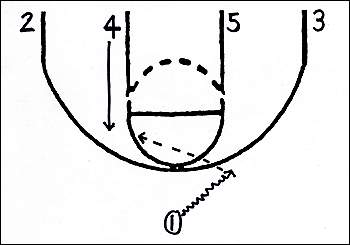

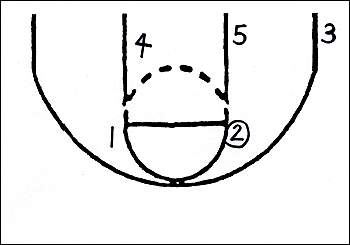

It is an offense that can found from the ACC to the WCC. Mark Few's Zags of Gonzaga, and Gary Williams' Maryland Terrapins, albeit a little differently, get a lot of mileage out of the flex offense. The basis of the offense, however, was introduced in the early 1970s by Carroll Williams of Santa Clara University. He is known as the "father" of the modern "flex offense. But Carroll Williams' assistant coach Dan Fitzgerald brought it north to Spokane as the head coach of Gonzaga and it has been a big part of the Zag's success ever since. The "flex" is a continuity (or pattern) man-to-man offense where all five players are interchangeable. It involves constant reversal of the ball from one side of the court to the other. It can also be described as a structured form of "motion offense". And, with patient ball movement and good screening, it can keep a defense on its toes for the entire 35-second shot clock. Whether out of the fast break or a half-court entry pass, the initial pattern, or basic spots on the court at team wants to fill in the "flex offense", are the two elbows, the two corners and the ball side block (or low post). As the ball is passed from the point guard (1) at the elbow to the power forward (4) at the opposite elbow, we back screen the cutter (3) out of the ball side corner and look for the pass inside for the lay up. Note that the small forward (cutter) makes his cut to the baseline side of the screen.

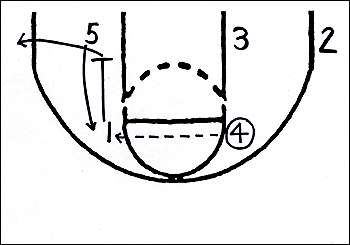

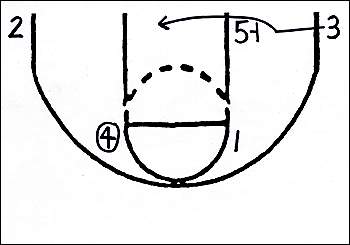

After the back screen by the center (5), the point guard (1) down screens for him and pops out to corner to create spacing. The post man (5) comes off the screen looking for the jump shot. Teams with a mobile big man, like Gonzaga's Zach Gourde, love this option.

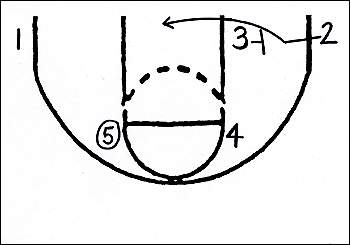

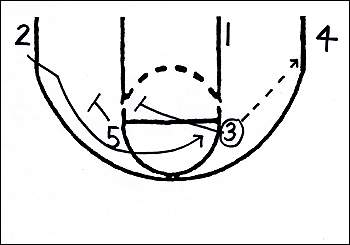

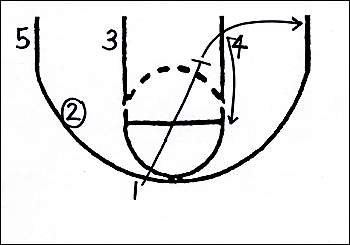

The continuity continues as the small forward (3) sets the back screen for the off-guard (2).

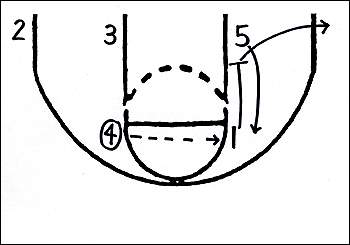

The next move is for the power forward (4) to down screen for the small forward (3), who comes to elbow looking for the jumper.

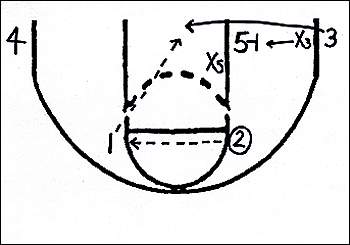

If the defender (X4) denies the pass to the power forward (4) at the elbow, it presents a great opportunity for a back-door lay up for the power forward. If this happens, it's up to the small forward (3) to replace the power foward at the elbow.

The "flex" continues as the post man (5) passes to the small forward (3) and the off-guard (2) back screens for the point guard (1).

Some teams like to throw the ball to the corner and set the staggered double screen away -- in this case for the off-guard (2). This action also isolates the point guard in the post.

When the ball comes out of the corner and is reversed from the power forward (4) to the off-guard (2) and ultimately to the small forward (3), it's up to the point guard (1) to set the back screen to keep the initial pattern going.

Gonzaga 'Flex'

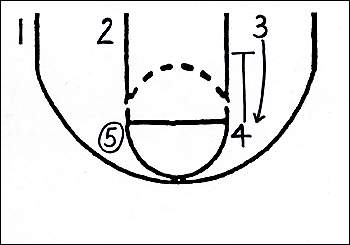

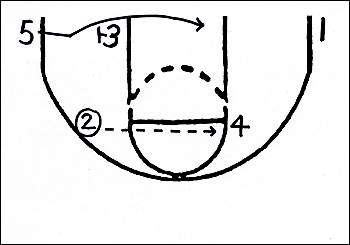

Now, if the small forward (3) doesn't come open off his cut, the point guard (1) sets a down screen for the power forward (4), who pops out to the corner.

On the pass out to the power forward (4) in the corner, the small forward (3) sets the back screen for the post man (5), who looks for a lay up.

The continuity simply continues as the off-guard (2) down screens for the small forward (3).

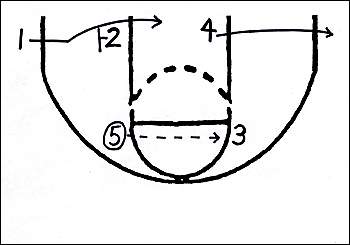

Another common entry to get into the flex offense is what we call the "1-4 low" set with four players on the baseline. Whichever way the point man dribbles, the opposite post man (4) flashes to the elbow to receive the pass.

As you can see, even though we have entered the ball from a different set, we can continue the continuity as we back screen for small forward (3).

Then, the down screen for post man (5).

Maryland 'Flex'

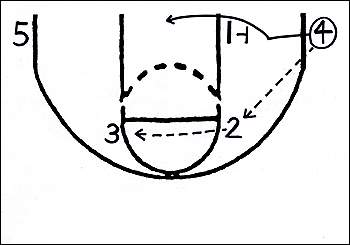

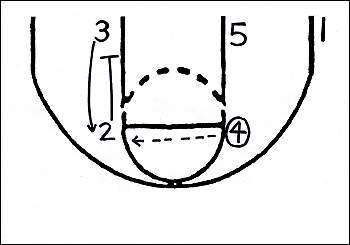

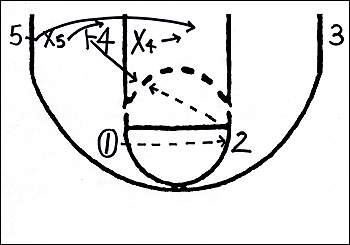

If the power forward (4) does not receive the pass from the off-guard (2), he pops out to the corner.

On the ball reversal back to the point guard (1), the post man or center (5) sets the back screen for the small forward (3). And, because the post defender (X5) does a poor job of helping his teammate, the point (1) is able to pass to the small forward (3) for a lay up.

Hopefully, this has given you a little flavor of the flex offense. Again, it has become popular at all levels of basketball, and its strengths lie a number of areas:

1. It has continuity and preys on a defensive breakdown.

Send in your Hoops 101 questions. Fran Fraschilla will answer a few each week as the season continues.

"Hello,

Jennifer, I like what you are emphasizing on offense and defense. As you get close to the postseason, it's always good to "spice up" your offense with a couple of new set plays, a new inbounds play, and, on defense, maybe a "trap" out of your 2-3 zone (check out our Syracuse 2-3 zone column from January 13). It will keep your players stimulated and give your opponents one more thing to think about.

"How does the four-corner offense work?"

Paul, In the mid-70's, Phil Ford, North Carolina's All-American point guard (and one of the best college guards of all time) became synonymous with the Four Corners. Keep in mind, there was no shot clock back then so when the Tar Heels got a 4- or 6-point lead, they held the ball and spread the court until they could get a lay up. You don't see this offense much in today's game because of the 35-second shot clock. Teams can pack in their defense and force you to attack them. In fact, before the shot clock, a variety of "delay games" were used to take time off the clock and spread the court. One last thing, Coach Smith would rightly credit another former Kansas Jayhawk alum and Basketball Hall of Famer John McLendon of North Carolina College and, later, at Tennessee State with using an original version of the Four Corners even earlier than the 1960's. McLendon would go on to be one of the game's great ambassadors.

"Hey Coach,

Todd, 1. The screener always has his "butt to the ball". This insures a proper screening angle so he can get as wide as he can. This makes it more difficult for the defender to fight through the screen. 2. The screener always gets his body on the defender. Again, you can't be afraid of contact. Watch John Stockton set screens for the Jazz. 3. The cutter always WAITS for the screen to be set. If he cuts early, his defender get though easier. 4. The screener only screens to his shooting range, because when his defender helps on the cutter, the screener can "pop out" for a shot in his range. Fran Fraschilla spent 23 years on the sidelines as a college basketball coach before joining ESPN this season as an broadcast analyst. He guided both Manhattan (1993, 1995) and St. John's (1998) to the NCAA Tournament in his nine seasons as a Division I head coach, leaving New Mexico following the end of the 2001-02 season. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||