|

||

| Inside the belly of the Monster By Jim Caple Page 2 columnist | ||

Miles: 92 (Springfield, Mass., to Boston); total miles: 3,390; hours of driving: 2; hours of sleep; 6; naked pedestrians dashing across Bolyston Street: 1; wrong turns while getting around the Big Dig: 4; parking across from Fenway: $25; Diet Pepsi: 5 units; miles remaining: 0.

In other words, I am enjoying a unique view of Fenway Park while also sharing the typical Bostonian's daily perspective of the world. After 17 days, nearly 3,400 miles, more than 160 gallons of gas and several cases of Diet Pepsi, my cross-country tour of sports along Interstate 90 is at its end. With Scooter flying home on his own, I drove the final stretch of our nation's longest highway earlier Wednesday afternoon, passing within a Nomar Garciaparra throw of Fenway Park before reaching the eastern terminus two miles later in the congestion of Boston's notorious Big Dig. For those who have never been to Boston, the Big Dig is a vast road construction project that has been disrupting traffic since about, oh, 1918, when the Red Sox last won the World Series, and probably will not be finished until the Red Sox win another World Series. Neither seems in the near future what with the traffic jam that awaited me and the recent city-quieting Red Sox slide. This is a city that loves its history, and that 84-year World Series drought is as much a part of the Boston identity as Paul Revere's Midnight Ride, the Kennedy family and the Cheers bar. The Celtics had the Russell and Bird dynasties, and the Patriots won last winter's Super Bowl, but it is the Sox and the World Series drought that are permanently etched in the city's soul. In Boston, you can hold a perfectly normal conversation with someone, discussing a topic totally unrelated to the Red Sox, baseball or even sports, only to have him suddenly mutter, "That (expletive) Buckner.'' All you can do is nod your head and say you understand.

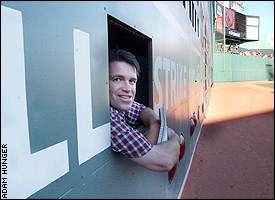

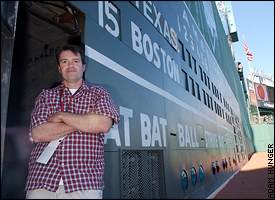

Go the distance. I also have always longed to watch a game from inside the scoreboard and, thanks to the Red Sox, I was able to end my I-90 tour here. And as I walked from beneath the grandstand, the Monster beckoned from a vast field of green so bright and inviting it practically glowed. "The novelty of that view never wears off," Rich Maloney says. Maloney is one of the stadium's two scoreboard operators (Chris Elias is the other), and this is his 13th season keeping score. He is a salesman during the day, and he says his Fenway gig is a superb ice-breaker to his sales pitches. "I tell people what I do, and it's always followed by 'You do what?' and 'You're the guy back there?' " Maloney says. "Almost everyone here in Boston is a die-hard Red Sox fan, and everyone knows the Green Monster. People tell me they bring their little kids to the games, and they just sit staring at the wall and looking at the scores change. They go, 'Who's back there? How did that change?' " It changes the same way it has since Ted Williams was in left field -- by hand -- and I get a quick demonstration when the Rangers' Kevin Mench leads off the game with a home run over the Monster. Maloney quickly picks up a thin green metal panel with a yellow 1 painted on it and inserts it in the inning slot for Texas. Elias inserts another 1 under the run total for Texas. One batter into the game and Boston is trailing. Again. You can hear fans groaning around New England. We peer through the slot at left fielder Rickey Henderson stretching and crouching and fidgeting, the latest in Boston's line of Hall of Fame outfielders. Of course, Henderson played the first 23 seasons of his career for other teams -- this is his first year with Boston. "We've seen him come through here in a bunch of different uniforms," Maloney says.

The oldest name remaining belongs to Jimmy Piersall, who scribbled his here in 1956. Tony Gwynn signed during the All-Star Game, but his name was recently covered by an electrical panel. Carlton Fisk signed and so did the rest of his family when the Red Sox retired his number a couple years ago. Chuck Knoblauch nearly went on the disabled list when the chair collapsed beneath him while signing his name. Mike Greenwell would visit Maloney and Elias during pitching changes. Even Matt Damon visited the scoreboard during the 1999 All-Star Game. "He came in and said, 'Wow, this place is great. I would trade jobs with you in a second,' Maloney says. "I was like, 'Gee, where do I sign up?' " Maloney laughs. He knows he isn't going anywhere, even if he could swap for a job that pays millions and includes filming love scenes with Franka Potente. After 13 years, this scoreboard is such a part of his life that he recently had a mural of the Green Monster painted on the wall of his basement rec room. The mural meticulously recreates the scoreboard from June 10, 2001, the day his son, John, was born. "I found out what color paint the Red Sox use and where they get it," he says. "The guy doing the mural was just going to paint it Kelly green and I had to say, 'Sorry, but it has to be the exact color.' " In other words, there's no need for aspiring scoreboard keepers to rush their applications to the Red Sox office. "I'm a typical Red Sox fan. I'm a pessimist. I know the year I stop doing it, they'll win it." Texas takes a 3-0 lead before the Red Sox begin rallying when Lou Merloni doubles home Jason Varitek in the fifth inning. Merloni is a local kid, who Maloney knows from youth ball. "I always tell him, 'I've got eight years of major-league experience on you, and he's always quick to tell me that he's on the right side of the fence.' "

I ask Maloney what it would be like if the Red Sox actually won the World Series, and he's the man who slips the final score onto the board. He smiles and shakes his head as he struggles to imagine the moment he's longed for his entire life. This is always a difficult thought for Red Sox fans. They have longed so desperately and so long for a World Series championship that they simply cannot imagine the emotions it would inspire. "Chris always says he'll retire when the Red Sox win the World Series, because there'll be nothing left to accomplish as a scorekeeper," Maloney says. "If they were lucky enough to win it, and I was lucky enough to be here, I don't know what could possibly bring me back. "Maybe I could realize the scorekeeper's dream and retire to the Teal Tower (the Marlins scoreboard) in Florida." The Red Sox score two in the sixth to tie the score, and No-mah singles home two runs in the bottom of the eighth inning to give Boston a 5-3 lead. The crowd roars and I slip another 2 into the scoreboard, feeling as if I have just done my little bit for the Red Sox playoff hopes. Looking out at the No. 9 the Red Sox mowed into the left field grass when Williams died two months ago, I think about how scorekeepers used to watch him play from this same vantage. "Ted could have the perfect tombstone: 1918-2002," Maloney says, linking Boston's last world championship with what could be their next if only the Red Sox can win it this year. "You look at the two years, and you can't help but think it's fate." Perhaps, but Williams doesn't have a tombstone because his son froze his body instead, the Red Sox trail the Yankees by seven games and the wild-card teams by 3½, and there might not even be a postseason, because the players have set a strike date of Aug. 30, which by a terrible coincidence, is Williams' birthday. The press box calls; the Mariners-Tigers game has just ended. I remove the 9 panel from the Seattle score, turning the 8-2 game into a final. With that simple action, I have reconnected with my hometown team even though I'm a long way from Detroit. I feel a sense of attachment and belonging beyond all logic.

"It's the first question they ask," he says. "I think there's a long list of people who want to do this job. If I took all the people up on their offers to get back here, I could retire." Boston's Ugueth Urbina closes out the game to seal the victory, and as soon at he records the final out, Maloney and Elias begin removing the panels from the ninth. The Red Sox haven't even reached the dugout, when Maloney removes the first team from the out-of-town scores. The two clear the scoreboard as swiftly as possible, though Maloney says they undoubtedly would leave a World Series-clinching score up as long as possible. "That would be the natural photo," he says. "Everyone would want to get that shot." I pause from helping him to take in the moment. This is the wall that has always meant baseball to me, and here it is, inches from my face, big and beautiful, broad and tall, gleaming as if Steven Spielberg personally oversaw its lighting. I have traveled so far and seen so much on this journey across I-90, but this might be my favorite moment of all, here at the end of the road, with that long interstate a mere two blocks behind the wall, as close to me as I am to home plate. Within minutes, the scoreboard is clear. Maloney and I say good-bye. He promises to e-mail a photo of his mural. Sports and I-90 have brought me another friend. I'm on my way out when I suddenly realize that, because the Mariners will be on the road until the Aug. 30 strike deadline, I might have just seen my last game of the season. I return to the field for one last look at the diamond that has been here since the Titanic went down, and the green Wall that has stood loyally over Fenway since Williams was called up. I study the field before me, memorizing every detail, trying to preserve this image so that it will always be with me. I wish I knew Mahoney's friend so I could have a mural of it painted on the wall of my house. I am smiling as the stadium lights go off and the field goes dark. It's time to go home. Jim Caple is a senior writer for ESPN.com. He can be reached at cuffscaple@hotmail.com. |

|

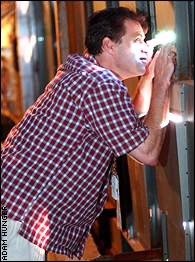

BOSTON -- I am looking out from inside the fabled Green Monster, staring through a narrow slit in the scoreboard that acts like blinders on a horse, restricting my view to nothing but the Red Sox playing before me, the Fenway Faithful cheering behind them and a scoreboard above them all that is flashing the score of the New York Yankees game.

BOSTON -- I am looking out from inside the fabled Green Monster, staring through a narrow slit in the scoreboard that acts like blinders on a horse, restricting my view to nothing but the Red Sox playing before me, the Fenway Faithful cheering behind them and a scoreboard above them all that is flashing the score of the New York Yankees game.