| ||||||||||||

ALSO SEE Go with the kids Go with the kids | ||||

| ESPN.com NFL | ||||

Tuesday, August 8

That big deal can turn dangerous

Special to ESPN.com

Editor's note: The team of writers from the Baseball Prospectus (tm) will be writing twice a week for ESPN.com. You can check out more of their work at their website at baseballprospectus.com.

Ken Griffey Jr., one of the best players in baseball and among its top gate attractions, is traded for a good but underwhelming package of talent. Randy Johnson, an impact player at a similar level, is traded for three good prospects, two of whom are now entrenched in one of baseball's best rotations.

Why such a difference? The Reds, Griffey's suitors this past offseason, didn't have to bid against anyone else, while the Astros, Johnson's suitors back in 1998, were bidding against half the teams in baseball. The history of bidding wars, both in baseball and in business, paints an unpretty picture for the "winners."

Twice a year, baseball whips itself into a frenzy by shuffling players around: at the trading deadline on July 31 and during the free-agent signing melee in December. The most-coveted players find multiple teams competing for their services, and a sort of auction develops in which the seller (the team holding the player, or the player and his agent) holds out for the highest bidder. If it's a trade, some reporter will declare the deal a Class One felony because he's never heard of any of the players in the deal beyond the marquee name.

But are teams just overpaying for talent? The history of deadline deals and massive free-agent contracts seems to indicate the latter. Willie Blair scored a huge free-agent contract after his 16-8 year in 1997 because of a perceived paucity of "quality" starting pitching that offseason. Andy Ashby fetched one of the top young pitchers in baseball in a trade earlier this month because he was seen as one of the few top starters available in trade. And Alex Rodriguez is headed for a windfall that will put his salary equal to the payroll of one or two teams -- a deal that will leave him hard-pressed to meet the expectations of his new employers.

The problem of wild-eyed optimists overpaying in auctions was first elucidated in 1971 in an obscure oil industry trade journal. Three engineers detailed the problem seen in auctions for oil drilling rights. Before bidding, each firm had its geologists examine the survey data to estimate how much oil the field probably holds. One firm's estimates may be lower than the actual amount of oil in the field. One firm's estimates will be about right. And at least one firm will predict estimates that are higher than the actual amount of oil in the field.

Because firms base their bids on their estimates, the firm with the most optimistic estimates will offer the most money for the drilling rights. So unless every firm underestimates the amount of oil in the field -- possible, but certainly not likely -- the firm that wins the auction will end up losing money on the deal because it overpaid at the start.

Now, instead of oil and drilling rights, think of baseball players and seven-year contracts. One general manager is always the most optimistic of all the GMs pursuing a particular player. There's always one GM who will look at a player with the rosiest of glasses, expecting the player to improve his performance or incorrectly evaluate his true ability. That GM is the one who wins the bidding war.

Ken Griffey Jr., one of the best players in baseball and among its top gate attractions, is traded for a good but underwhelming package of talent. Randy Johnson, an impact player at a similar level, is traded for three good prospects, two of whom are now entrenched in one of baseball's best rotations.

Why such a difference? The Reds, Griffey's suitors this past offseason, didn't have to bid against anyone else, while the Astros, Johnson's suitors back in 1998, were bidding against half the teams in baseball. The history of bidding wars, both in baseball and in business, paints an unpretty picture for the "winners."

Twice a year, baseball whips itself into a frenzy by shuffling players around: at the trading deadline on July 31 and during the free-agent signing melee in December. The most-coveted players find multiple teams competing for their services, and a sort of auction develops in which the seller (the team holding the player, or the player and his agent) holds out for the highest bidder. If it's a trade, some reporter will declare the deal a Class One felony because he's never heard of any of the players in the deal beyond the marquee name.

But are teams just overpaying for talent? The history of deadline deals and massive free-agent contracts seems to indicate the latter. Willie Blair scored a huge free-agent contract after his 16-8 year in 1997 because of a perceived paucity of "quality" starting pitching that offseason. Andy Ashby fetched one of the top young pitchers in baseball in a trade earlier this month because he was seen as one of the few top starters available in trade. And Alex Rodriguez is headed for a windfall that will put his salary equal to the payroll of one or two teams -- a deal that will leave him hard-pressed to meet the expectations of his new employers.

The problem of wild-eyed optimists overpaying in auctions was first elucidated in 1971 in an obscure oil industry trade journal. Three engineers detailed the problem seen in auctions for oil drilling rights. Before bidding, each firm had its geologists examine the survey data to estimate how much oil the field probably holds. One firm's estimates may be lower than the actual amount of oil in the field. One firm's estimates will be about right. And at least one firm will predict estimates that are higher than the actual amount of oil in the field.

Because firms base their bids on their estimates, the firm with the most optimistic estimates will offer the most money for the drilling rights. So unless every firm underestimates the amount of oil in the field -- possible, but certainly not likely -- the firm that wins the auction will end up losing money on the deal because it overpaid at the start.

Now, instead of oil and drilling rights, think of baseball players and seven-year contracts. One general manager is always the most optimistic of all the GMs pursuing a particular player. There's always one GM who will look at a player with the rosiest of glasses, expecting the player to improve his performance or incorrectly evaluate his true ability. That GM is the one who wins the bidding war.

| |

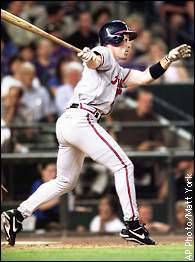

| The Braves traded for the veteran B.J. Surhoff despite the fact that he is just a career .281 hitter. |

|

ESPN INSIDER

Copyright 1995-2000 ESPN/Starwave Partners d/b/a ESPN Internet Ventures. All rights reserved. Do not duplicate or redistribute in any form. ESPN.com Privacy Policy. Use of this site signifies your agreement to the Terms of Service. | ||||