By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

Alphabetically and arithmetically, what could be finer than having "Aaron, Hank" as the first name listed in The Baseball Encyclopedia? The book's leadoff man is better recognized as the cleanup hitter who holds the Cadillac of baseball records: His 755 home runs are the most by a major leaguer.

| |

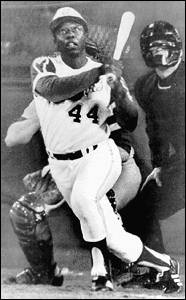

| Hank Aaron saw his name bypass Babe Ruth's on this April 8, 1974 swing of the bat. |

A lifetime .305 hitter, Aaron did most his damage for the Braves, first in Milwaukee (1954-65), then in Atlanta (1966-74), before finishing his 23-year career with the Milwaukee Brewers (1975-76).

"The thing I like about baseball is that it's one-on-one," Aaron said. "You stand up there alone, and if you make a mistake, it's your mistake. If you hit a home run, it's your home run."

Aaron's crowning moment was, of course, a home run. It came when he surpassed what had seemed like an unbreakable record only a decade earlier. That was the night in 1974 he walloped No. 715 and trotted around the bases past the Babe and into history.

While Aaron had the numbers, he didn't have much fan appeal. He was considered hard working, humble and shy, just as Joe DiMaggio was. But while those qualities made DiMaggio a hero, they made Aaron an enigma. Aaron was often overlooked as one of the game's greats until he took off on his chase of the Bambino. Racism had something to do with it, as well as his playing in the Atlanta and Milwaukee markets.

Aaron was born Feb. 5, 1934, in a part of Mobile, Ala., called Down The Bay, a poor area of town populated mostly by blacks. The family moved to a better area of Mobile called Toulminville, where he was raised. In high school, Aaron played shortstop and third base and was an outstanding hitter though he batted cross-handed.

|

At spring training the next year, it didn't look like the 20-year-old Aaron would make the Braves. But then Bobby Thomson (yes, the Bobby Thomson of Ralph Branca fame) suffered a broken ankle sliding into second. The Braves needed an outfielder to replace Thomson, and the 6-foot, 160-pound Aaron won the competition, taking over as the regular left fielder.

He hit his first home run on April 23, 1954 off of the Cardinals' Vic Raschi. In 122 games, he batted .280 (he wouldn't hit that low again until 1966) with 13 homers (he wouldn't go below 20 for the next 20 years) before suffering a broken ankle on Sept. 5.

In 1955, Aaron moved to right field, where he remained for most of his career (and won three Gold Gloves). He batted .314 with 27 homers and 106 RBI. This was just the start. The next season, he won his first of two National League batting titles with a .328 average. (In 1959, he won the crown with a career-best .355.)

Two changes were made in 1957. Aaron went from second in the batting order to fourth, behind Eddie Mathews instead of in front of him, and he switched from a 36-ounce bat to a 34-ounce model. Aaron responded by leading the league with 44 homers (one of four times he would hit his uniform number) and a career-high 132 RBI while batting .322.

When Aaron drilled a pitch from the Cardinals' Billy Muffett for a two-run homer in the 11th inning of a game in late September, it clinched the Braves' first pennant in Milwaukee and Aaron was carried off the field by his teammates. Aaron, 23, won his lone MVP that year.

Milwaukee registered its only World Series behind right-handed pitcher Lew Burdette, who defeated the Yankees three times. Aaron did his part by hitting .393 with three homers and seven RBI.

Aaron (.326, 30 homers, 95 RBI) led the Braves to another pennant in 1958, but this time the Braves lost a seven-game Series to the Yankees. As the years went on, so did the homers. While the 6 foot Aaron would fill out -- he would reach 190 pounds -- he never was a heavy man. The key to his hitting seemed to be his supple, powerful wrists that allowed him to crack his bat like a buggy whip.

The chase to beat the Babe heated up in the summer of 1973. So did the mail. Aaron needed a secretary to sort it as he received more than an estimated 3,000 letters a day, more than any American outside of politics. Unfortunately, racists did much of the writing. A sampling:

"Dear Nigger Henry,

You are (not) going to break this record established by the great Babe Ruth if I can help it. ... Whites are far more superior than jungle bunnies. . My gun is watching your every black move."

"Dear Henry Aaron,

How about some sickle cell anemia, Hank?"

The letters came from every state, but most were postmarked in northern cities. They were filled with hate. More hate than Aaron had ever imagined. "This," Aaron said later about the letters, "changed me."

The summer of '73 ended with Hammering Hank at 713 homers after hitting a remarkable 40 in just 392 at-bats. He was 39.

In his first at-bat in 1974, Aaron homered off Cincinnati's Jack Billingham, tying Ruth. His eyes got teary as he rounded third base. That night he called his mother. "I'm going to save the next one for you, Mom," he said.

On April 8, 1974, the largest crowd in Braves history (53,775) came out to witness history. Aaron didn't disappoint. In the fourth inning, he ripped an Al Downing pitch into the Braves bullpen, where it was caught by reliever Tom House. As Aaron rounded second base, two college students appeared and ran alongside him before security stepped in. The new home run king was mobbed at home by his teammates.

A quarter of a century later, Aaron still has the record -- and the hate mail. "I read the letters," he said, "because they remind me not to be surprised or hurt. They remind me what people are really like."

After retiring as a player, Aaron became one of the first blacks in Major League Baseball upper-level management as Atlanta's vice president of player development. Since Dec. 1989, he has served as senior vice president and assistant to the president, but he is more active for Turner Broadcasting as a corporate vice president of community relations and a member of TBS' board of directors. He also is vice president of business development for The Airport Network.