By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

The combination of competing in both 200 meters and 400 meters is rare. Not often in history do we find a fast man with so much endurance -- or an endurance man with so much speed.

| |

| Michael Johnson enjoyed 400 finals victory streak of 58 races, stretching eight years. |

Enter Michael Johnson.

"There's always been a stereotype," Johnson said. "If you ran the 200, you also ran the 100. If you ran the 400, that was all you did."

He started with the 200, and unlike most runners, he went up in distance, not down. With Georgia 1996 on his mind, he announced his intention of becoming the first man to win both the 200 and 400 at the same Olympics. Call it a double dare of the highest order. Especially coming from a man who had failed in his two previous Olympics; once because of injury, once because of illness.

But Johnson came with the proper credentials -- the No. 1 ranking in the world five times in the 400 and four times in the 200 in the 1990s. He was the first man to break both 44 seconds in the 400 and 20 seconds in the 200.

He warmed up for the 1996 Atlanta Olympics with two dress rehearsals. He won both titles at the U.S. national championships in June 1995 in Sacramento, Calif., becoming the first man to take both races at a major meet since Maxie Long at the U.S. championships in 1899.

Two months later, in Goteborg, Sweden, Johnson repeated the double -- unprecedented at the world championships. His 43.39 in the 400 was the second fastest in history, a tenth of a second behind Butch Reynolds' 43.29.

At the Olympic Trials in June 1996 in Atlanta, the muscular 6-foot-1, 180-pound Johnson won both races again. In the semifinals of the 200, he achieved his longtime goal of erasing Pietro Mennea's record of 19.72 for the 200, finishing in 19.66. He was primed.

"What this means is history," Johnson said. "There are two household names in the history of track and field -- Jesse Owens and Carl Lewis. I'm in position to be the third. It'll be the biggest show of the Olympics. I'm going to be The Man at these Olympics."

As they say, if you can walk the talk (or in Johnson's case, run the races), it ain't bragging.

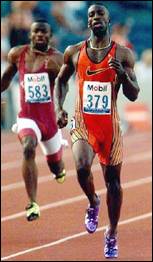

Firing on all burners, Johnson, wearing customized, symbolically gold-colored track shoes, set an Olympic record of 43.49 in winning the 400 on July 29. Three days later came the 200 finals. His competition included Frankie Fredericks, who had ended Johnson's two-year winning streak in this event four weeks earlier.

At the gun, Johnson reacted quickly, but four steps into the race, he stumbled slightly. But he recovered, caught Fredericks at 80 meters, and then went into a gear unknown by man. With some 80,000 fans screaming, Johnson's gold shoes crossed the finish line in an incredible 19.32 seconds.

Bronze medalist Ato Boldon made a comic bow to the king of the track, and pointed to the clock. "Nineteen-point-thirty two," Boldon said. "That's not a time. It sounds like my dad's birth date."

|

|

| Previous poll results |

Johnson was born Sept. 13, 1967 in Dallas, the youngest of five children. His parents -- Paul Johnson Sr., a truck driver, and Ruby Johnson, an elementary school teacher -- emphasized education, and Michael was regularly placed in classes for gifted children.

He was involved in track and football but quit the latter in junior high school after two years. "I'm not a person who likes someone screaming and hollering at me," he said. "The football environment is too much aggression. You have to have some aggression on the track, but it's not the same."

With his erect running style, he looked like a statue. Baylor recruited him as a sprinter for relays. "I'd be lying if I said I thought Michael was going to be a world-class sprinter," said Baylor coach Clyde Hart. "I don't think anybody did."

But he did become world class, and rather quickly, with the 200 being his best race while he learned the intricacies of the 400. But before the Olympic Trials in 1988, he developed a stress fracture on his left fibula. He didn't qualify in the 400 and then he skipped the 200 altogether.

He graduated from Baylor with a bachelor's degree in business in 1990, having won five NCAA championships during his career. In an unprecedented accomplishment, he was the first athlete to be ranked No. 1 in the world in both the 200 and 400 in a career, much less the same year.

In preparing for the 1992 Olympics, Johnson and Hart decided that the runner would concentrate on the 200 to the exclusion of the 400. Two weeks before the Olympics opened in Barcelona, after a warmup meet in the Spanish city of Salamanca, Johnson and his agent were on their way to dinner at a Burger King. At the last second, they changed their mind when they saw El Candil, the Spanish restaurant they had enjoyed the previous night.

So they returned, and dined on a mixture of grilled and smoked meats again. Only this time, both men came down with food poisoning. Even after the sickness passed, Johnson found the weight loss had sapped his strength. Considered a sure thing at the Olympics, he was eliminated in the semifinals as 11 runners beat his pedestrian 20.78.

"My dad was even worried I'd do something crazy that night in Barcelona," Johnson said. "But I've always seen track as a job that I love. It's not who I am. I'd had so much success up to that point, I'd already proved I was the best."

To himself. And to his competitors. But not to the public. Olympic medals are worth more than their weight in gold.

Johnson did get an Olympic gold for his participation on the winning 4x400 relay team, but that's not the same as an individual gold. He had to wait four more years for that.

"He is a man with nothing in his personal life to distract him, nothing in his emotional makeup to undermine him; in short there is nothing controllable that he will fail to control," wrote Gary Smith in Sports Illustrated. "He is an arrow shaved of all superfluity, feathered strictly for aerodynamics, drawn and discharged with the barest expenditure of motion, an arrow streaming nowhere except to its target."

And that target was Atlanta. A meticulous man, Johnson records everything in his electronic organizer. His filing cabinet is impeccably maintained. He plans for every possible hindrance. He doesn't rush to make decisions. He calls himself the ultimate realist.

"A rare man, the world's best sprinter: He is the tortoise and the hare," Smith wrote.

In the 200, he was the hare. His race will go down as one for the ages. Johnson thought he could run a 19.5, but he never considered a 19.32. In the dash events, records normally are broken by a few hundredths of a seconds, not 34 hundredths in one swoop.

In June 1997, Johnson's 58-final, eight-year winning streak in the 400 ended in Paris as he finished fifth, with Antonio Pettigrew winning the race. But Johnson came back that summer to win his fifth individual World Championships gold, taking the 400.

Johnson has changed from modest to macho man. "I'd like to be remembered as nothing more than what I am, the most consistent and versatile sprinter who ever sprinted," he said. "No one has ever done what I've done over a period of times at the distances I've run."