By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

The early 1960s were considered a modern Camelot, with a vigorous President energizing the country and a beautiful wife standing by his side.

| |

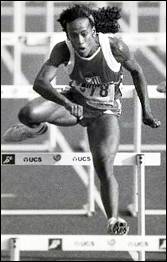

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee was an all-around athlete, but her explosiveness was her main weapon. |

Jeane Dixon couldn't have made a better prediction. Jackie Joyner did become the first lady of something: Track and field.

She came to dominate the heptathlon, a demanding seven-event competition that measures speed, strength and stamina. Not only the possessor of the world record of 7,291 points, she also holds the next five highest scores. She was the first to register more than 7,000 points in the event, which consists of the 100-meter hurdles, high jump, shot put, 200 meters, long jump, javelin and 800 meters.

After gaining an Olympic silver medal in 1984 when she was edged by less than a second for first, she captured gold at both the 1988 and 1992 Games. "She's the greatest multi-event athlete ever, man or woman," said Bruce Jenner, an expert on multi-events as the 1976 Olympic decathlon champion.

In the long jump, she tied the then-world record of 24 feet, 5½ inches at the 1987 Pan-Am Games. By winning a gold (1988) and two bronzes (1992 and 1996) in that event, she became the most decorated woman in U.S. Olympic track and field history with six medals total.

In her rise to excellence, she overcame poverty and tragedy, discrimination and disease. Sport was her way out. "I don't think being an athlete is unfeminine," she said. "I think of it as a kind of grace."

Her path to greatness was made easier thanks to the people who loved her deeply.

"She was shaped by a mother who bound her to excellence, by an older brother who was an admirer, defender and soul mate, and by a coach who demanded the best use of her gifts and did it so selflessly that she eventually married him," wrote Kenny Moore of Sports Illustrated. "Whereupon she bloomed even more grandly."

Joyner's mother Mary was 16 when she married 15-year-old Alfred Joyner. The oldest of their four children was Al Joyner, who would become the 1984 Olympic triple jump champion and later marry sprinter Florence Griffith. Then came Jackie, on March 3, 1962.

There was a liquor store and pool hall across from the Joyner house, which was little more than wallpaper and sticks, with four small bedrooms. "I remember Jackie and me crying together in a back room in that house, swearing that someday we were going to make it," Al said. "Make it out. Make things different."

At 11, Jackie saw a man gunned down outside her house. A few years later, she spoke to her grandmother on the telephone, only to find out the next day that her grandfather had gotten drunk and shot his wife with a shotgun while she was asleep.

Jackie was growing up too fast ("even at 10 or 12, I was a hot, fast little cheerleader") for her young -- but old-fashioned -- mom. Mary slowed her down. She told Jackie she couldn't date until she was 18.

|

After graduating in the top 10 percent of her class of 350, she went west, to UCLA, to play basketball (she started as a forward for four years), to compete in track and field, and to escape her strict mother. But in January 1981, the 18-year-old freshman had to return home when a rare form of meningitis suddenly struck Mary.

She was in a coma, brain dead, when the family visited in the hospital. Alfred couldn't remove the life-support system on his wife, so it was left to Jackie and Al to make the decision to do it. Mary was 37.

When Joyner returned to UCLA, she was offered comfort by Bob Kersee, an assistant track coach but someone she didn't know well. "He told me that his mother had also died when he was young and he'd be there if I needed someone to talk to," Joyner said. "He let me know he cared about me as a person as well as an athlete."

As an athlete, Kersee saw Joyner's potential and became her coach, improving her skills considerably in the heptathlon. A Marine sergeant when training her, he was more tender in private. Eventually, he proposed to her at the Astrodome, with Nolan Ryan pitching.

"I decided to try a fastball on her," he said. "I said, 'I would like to marry you. Would you like to marry me?'" She thought it over for a day or so, then agreed. They married on Jan. 11, 1986, in Long Beach, where Kersee was an associate pastor.

By this time, Jackie had her Olympic silver medal. A poor long jump performance kept her lead over Australia's Glynis Nunn down to 31 points as they took off in the final event, the 800 meters. Jackie, whose left leg was bound with a hamstring wrap, could lose to Nunn by 2.13 seconds, or about 14 yards, and win the gold.

Jackie lost by 2.46 seconds, a third of a second too slow. Nunn finished with 6,390 points, Joyner with 6,385.

By 1988, the 5-foot-10, 150-pound Joyner-Kersee was the overwhelming gold medal favorite. She had won nine consecutive heptathlons since that 1984 Olympic defeat. She broke the 7,000-point barrier with 7,148 at the Goodwill Games on July 7, 1986 and became Joyner-Kersee (Bob told her she couldn't take his name until she set a world record). She broke that mark a month later at the Olympic Festival with 7,158, and then beat it again at the 1988 Olympic Trials with 7,215.

In 1987 at the World Championships in Rome, after winning the first of two heptathlon and long jump world titles, she was pictured on the cover of Sports Illustrated with the title: "Super Woman."

At the 1988 Games in Seoul, she performed -- what else? -- super, setting the still-standing world record of 7,291 points in the heptathlon. Five days later, she won her second gold, leaping an Olympic record 24-3½ in the long jump.

"Her performances are like a great opera or concert," Kersee said. "I feel like I should be wearing a tux when I watch them."

Not everybody felt that way. Some accused her of using drugs to enhance her performance, but she has never failed a drug test.

More troubling was her asthma, which she discovered she had in 1983. Later on, she would have several full-blown attacks, and sometimes would wear masks while competing.

In the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, Joyner-Kersee retained her heptathlon title, registering 7,044 points. However, she finished third in the long jump at 23-2½.

At the 1996 Games in Atlanta, a teary-eyed Joyner-Kersee withdrew from the heptathlon because of a troublesome right hamstring after running the hurdles. Still hurting, she competed in the long jump and, on her final leap, went 22-11¾, good for a bronze medal by 1¼ inches. "It definitely was a medal of courage," Kersee said.

Later that year, she joined the Richmond Rage of the newly formed American Basketball League but played sparingly, averaging less than a point a game.

She retired from track in the summer of 1998, but Joyner-Kersee isn't looking backward. "It's better to look ahead and prepare," she said, "than to look back and regret."