By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

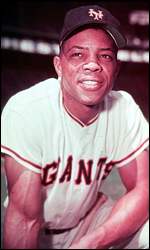

The 20-year-old kid with the bright, boyish smile entered the majors tentatively, like a child peeking into a forbidden room. But he soon realized that he did indeed belong, that he wasn't an interloper. Not only did he play the game with extreme skill, but for most of his 22-year career, he made the game seem like, well, fun.

| |

| The Say Hey Kid mastered the five fundamentals of baseball. |

There always was something fresh and pleasurable in his performance. Making a glove-thumping basket catch or a whirling throw in centerfield, losing his hat running the bases or swinging from his heels at the plate, Willie Mays played with an irresistible, unrelenting exuberance.

"I can never understand how some players are always talking about baseball being hard work," Mays said during his first decade in the game. "To me, it's always been a pleasure, even when I feel sort of draggy after a doubleheader."

It's like Brooklyn Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella said, "You gotta be a man to play baseball for a living, but you gotta have a lot of little boy in you, too."

Willie had both, whether he was making an impossible catch of a Vic Wertz drive in the World Series or hitting the ball for three sewers with a broomstick when playing stickball with kids in Harlem.

"When Mays is poised in the outfield or at bat he seems more eager, or anxious, than anybody else," Roy Blount Jr. wrote in Sports Illustrated. "He has the air of that kid in a pickup game who has more ability and fire than the others and wishes intensely that they would come on and play 'right' and raise the whole game to a level commensurate with his own gifts and appetites."

The Giants centerfielder (first in New York, then San Francisco) was the complete player. Baseball people like to speak of the five tools in the same way others believe in the Ten Commandments. There's hitting, hitting for power, running, fielding and throwing. The 5-foot-11, 185-pounder with the massive flat chest and bulging arms and shoulders was superb in all five categories.

The Say Hey Kid won two MVPs, 11 years apart. He hit 660 home runs (third most in history), is one of only four players to twice hit more than 50 homers in a National League season and belted four homers in a game. He is a member of the elite 3,000-hit club (3,283, No. 10 all-time) and has a lifetime average of .302. His 2,062 runs rank fifth and his 1,903 RBI eighth.

He was the first player to hit 300 homers and steal 300 bases (338 total). He led the National League in steals four consecutive seasons and on the bases his daring running made pitchers crazy, destroying their concentration and making it easier for the hitters who followed him in the lineup.

The Gold Glove came into existence in 1957 and Mays earned one each of the first 12 years. He is the only outfielder with more than 7,000 career putouts (7,095). A half-dozen or so of his catches are legendary, with the Wertz catch being the most famous though it probably wasn't his best.

Despite his showmanship (he intentionally wore his cap a size too small so it would fall off), he broke the game down to its simplest form. "When they throw the ball, I hit it," he said. "When they hit the ball, I catch it."

Mays was born on May 6, 1931 in Westfield, Ala., a grimy steel-mill town near the outskirts of Birmingham. Even before he was old enough to walk, his father, Willie Sr., rolled a ball back and forth with him. When dad stopped, Willie cried.

After his parents divorced when he was a toddler, Mays lived with an aunt in nearby Fairfield. He was raised in a state of segregation -- at the movies, at restaurants, at bathrooms that were marked "colored" and "white."

His father, who lived nearby, and an uncle oversaw Willie's athletic development. "I never saw a boy who loved baseball the way Willie always did," his father said.

In high school, Willie starred in football and basketball as his school did not have a baseball team. However, he was a good enough outfielder to play for the Birmingham Barons, his father's former Negro League team.

After graduation, Mays signed with the Giants for $6,000. After tearing up Class B pitching with Trenton (.353 in 81 games in 1950) and Class AAA pitching with Minneapolis (.477 in 35 games in 1951), the Giants summoned the prodigy.

|

The 20-year-old Mays didn't think he was ready for the majors. When he started out 1-for-26 -- the one hit was a homer off future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn in his 13th at-bat -- his confidence waned. But Giants manager Leo Durocher, whom Mays called Mr. Leo, stroked the uncertain youngster. Mays responded to this kid-glove treatment and proceeded to win Rookie of the Year with his 20 homers, 68 RBI and .274 average in 121 games.

His play and enthusiasm sparked the Giants to the "Miracle of Coogan's Bluff." They went from 13 games behind the hated Dodgers on August 11 to beating them in the playoffs on Bobby Thomson's ("The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!") homer.

He played 34 games in 1952 before being drafted into the Army, where for 21 months he swung his bat more than he shot his rifle, as he played in some 180 games. The anticipation was overwhelming for the Say Hey Kid's return in 1954. He didn't disappoint.

In his first full season, he earned the MVP by leading the majors with a .345 average, hitting 41 homers, knocking in 110 runs and scoring 119 (the first of 12 consecutive seasons with at least 100 runs). Mays' unbelievable back-to-the-plate catch of Wertz's 450-foot blast saved the first game of the World Series and spurred the Giants to a stunning sweep of the favored Cleveland Indians.

The next season Mays became just the seventh player in history to hit 50 homers, with his 51 dingers winning him the first of four home-run titles.

During the fifties, until the Giants and Dodgers fled New York for California after the 1957 season, arguments constantly raged throughout the five boroughs over who was better: Willie, Mickey or the Duke? (If you need last names on Mickey and the Duke, you should be on another web site.)

In San Francisco, though Mays continued to play brilliantly, he wasn't revered the way he had been in New York. "Mays never was to San Francisco what he was to New York," wrote newspaperman Dick Young. "When the Giants moved to California, the San Francisco fans saw Mays as 'of' New York. And like any great city, they resent being followers."

Mays' major-league-high 49 homers and career-best 141 RBI led the 1962 Giants, with his game-winning homer in the regular-season finale moving San Francisco into another playoffs. Like 1951, it also was against the Dodgers. Like 1951, the Giants won the final game with a ninth-inning rally.

Three years later, Mays led the majors with 52 homers and won his second MVP. He began a downhill slide in 1967, and in 1972 he was traded back to New York, with the Mets. In his twilight, Mays tarnished his career by playing his final seven seasons more in quest of money than exuberance.

He was elected into the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 1979. Later that year Commissioner Bowie Kuhn banned him from baseball because he worked as a goodwill ambassador for an Atlantic City casino. The next commissioner, Peter Ueberroth, reinstated him in 1985.

Returning to the Giants in 1986, Mays now serves as a special assistant to the team president, a job more ceremonial than hard work.