By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

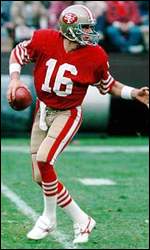

There's an old cartoon that shows everybody panicking, except for one guy, who is unruffled as he does his assigned task. In real life, that person is Joe Montana.

| |

| Joe Montana was MVP in three of his four Super Bowls, and led his team on The Drive in the other. |

He possessed an almost mystical calmness in the midst of chaos, especially with the game on the line in the fourth quarter. While others saw turmoil and danger after the snap, Montana saw order and opportunity. He was Joe Cool, the unflappable king of the comeback.

Take the 1989 Super Bowl against the Cincinnati Bengals. The San Francisco 49ers were down by three points with 3:20 left when Montana spotted -- no, not an open receiver -- but a personality. "There, in the stands, standing near the exit ramp," Montana said to tackle Harris Barton. "Isn't that John Candy?" And then he led the 49ers 92 yards, throwing for the winning touchdown with 34 seconds left.

This was one of Montana's 31 fourth-quarters comeback in the NFL.

Montana was neither exceptionally fast nor tall nor did he have a bazooka for an arm. The man whom his high school quarterbacks coach said "was born to be a quarterback" won by wits and grace, style and reaction. It was if he saw the game in slow motion. Whether it was with Notre Dame or the 49ers, whether the game was played in an ice storm in Dallas or in the humidity of Miami, Montana was The Man in the fourth quarter.

"There have been, and will be, much better arms and legs and much better bodies on quarterbacks in the NFL," said former 49er teammate Randy Cross, "but if you have to win a game or score a touchdown or win a championship, the only guy to get is Joe Montana."

Sports Illustrated headlined a story on the fragile-looking quarterback as "The Ultimate Winner." Montana won four Super Bowls in four appearances and became the only player to earn the Roman numeral game's MVP three times (and the other contest was the game-winning drive).

In these four games, he put up Super numbers, completing 83-of-122 passes (68 percent) for 1,142 yards with 11 touchdowns and no interceptions. His quarterback rating was 127.8 (while nobody outside the Elias Sports Bureau knows how to compute this rating, or even what it means, it is known that 127.8 is a figure beyond that of mortal men).

He made the throw on the play that became known as The Catch. That's when a scrambling Montana, with three Cowboys closing in for the kill, lofted the ball in the end zone to Dwight Clark. The six-yard touchdown pass, with 51 seconds left, gave the 49ers a 28-27 victory over Dallas for the 1981 NFC championship.

"At his best, when Joe was in sync, he had an intuitive, instinctive nature rarely equaled by any athlete in any sport," said Bill Walsh, his San Francisco mentor and coach, said about the two-time NFL MVP.

As a redshirt junior at Notre Dame in 1977, after sitting out the previous season because of a separated shoulder, Montana took the Irish to a national championship. In his career he led them to five improbable fourth-quarter comebacks (deficits ranging from eight to 22 points).

The most dramatic of them was his last collegiate game, at the 1979 Cotton Bowl, when he fought hypothermia in the ice and wind in Dallas. After being fed bouillon during the second half to get his temperature back near normal, he led Notre Dame from a 34-12 deficit to a 35-34 victory in the final 7:37, throwing a perfect pass to Kris Haines for a touchdown with no time remaining.

"Joe was born to be a quarterback," said Jeff Petrucci, his high school quarterback coach. "You saw it in the midget leagues, in high school -- the electricity in the huddle when he was in there. How many people are there in the world, three billion? And how many guys are there who can do what he can do? Him, maybe (Dan) Marino on a good day. Perhaps God had a hand in this thing."

Montana had a quick setup, nifty glide to the outside, the ability to scramble but under control, buying time, looking for a receiver underneath. And this was when he still was in high school.

Montana's roots are in western Pennsylvania, the cradle of quarterbacks. Marino, Johnny Unitas, Johnny Lujack, Joe Namath, George Blanda, Jim Kelly and Terry Hanratty are from the area. All were tough, dedicated, hard workers and competitive. "We had a no-nonsense, blue-collar background," Unitas said.

Montana was born in New Eagle on June 11, 1956, the only child of Joe Sr. and Theresa, and raised in nearby Monongahela. The family lived in a two-story frame house in a middle-class neighborhood and Joe Sr. helped his son get involved with sports.

Young Joe played baseball (three perfect games in the Little League) and basketball (he was offered a scholarship to North Carolina State), but after becoming a Parade All-American quarterback as a high school senior, he followed his idol, Hanratty, to Notre Dame.

At one-time a seventh-string quarterback, he was still No. 3 when the 1977 season started. But in the third game, with once-beaten Notre Dame losing 24-14 to Purdue, The Comeback Kid came off the bench to throw for 154 yards and a touchdown in the final 11 minutes to lead the Irish to a 31-24 victory.

Coach Dan Devine finally saw the light and installed Montana as his starter. Notre Dame didn't lose again, and won the national title by defeating No. 1 Texas 38-10 in the Cotton Bowl.

After capping his collegiate career with the comeback against Houston the following January, Montana was selected by the 49ers in the third round of the 1979 draft, the No. 82 overall selection. Walsh brought him along slowly and it wasn't until late in his second season that Montana became the starter.

|

In 1981, the 6-foot-2, 195-pound Montana was in complete control of Walsh's West Coast offense, and he led he 49ers to a 13-3 record. They won the NFC title with The Catch, and defeated Cincinnati 26-21 in the Super Bowl.

Returning to the Super Bowl three years later against the Miami Dolphins, Montana upstaged Marino, who had thrown for a record 48 touchdowns. He passed for 331 yards and three touchdowns in a 38-16 San Francisco rout.

Montana suffered a ruptured disk throwing a pass in the 1986 opener and underwent two-hour back surgery. Doctors told him it might be better for his health if he gave up football. Two months later, he was back, throwing three touchdown passes to Jerry Rice. But the season ended the way it had began -- in pain. Montana was knocked out of a 49-3 playoff loss to the Giants when noseguard Jim Burt, a future teammate, buried his helmet under Montana's chin.

Three years later, Montana had another Super Bowl ring. After spotting Candy in the stands, Joe Cool smoothly hit eight-of-nine passes, with his 10-yard strike to John Taylor giving the 49ers a 20-16 victory in Miami.

The next season, under George Seifert, Montana took the 49ers to a 14-2 record. San Francisco won its postseason games by 28, 27 and 45 points (55-10 over Denver in the Super Bowl) and Montana completed 78 percent of his passes for 800 yards, 11 touchdowns (five against Denver) and no interceptions.

An elbow injury caused Montana to miss 1991 and further complications caused him to sit out until the final game of 1992. With Steve Young entrenched at quarterback, Montana was traded to Kansas City in 1993. He led the Chiefs into the playoffs in his two seasons with them before deciding that, at age 38, he was finally weary of the game.