By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

Who ever thought that the kid in grade school who built volcanoes, dissected frogs, collected fossils and launched homemade rockets would become one of the most distinguished track athletes in history?

| |

| Edwin Moses wants to be remembered as the "guy nobody could beat." |

Even in high school, the serious youngster himself had no illusions of grandeur. "I had no ambitions to be an Olympic track star or any kind of athlete," he said.

But that's what happened to the analytical and practical Edwin Moses, the possessor of one bachelor's of science degree in physics, one master's in business administration, two Olympic gold medals and 107 consecutive victories in 400-meter hurdles finals.

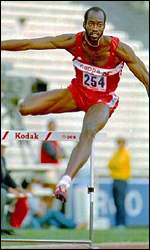

This athletic marvel enjoyed a run of nine years, nine months and nine days between losses. Four times he broke the world record. Neither his competitors nor his dreams could keep up with his performances. Bounding over the 10 three-foot hurdles, taking an unprecedented 13 steps between hurdles instead of the usual 14, he was a remarkable combination of speed, grace and stamina.

For much of his career, Moses was not appreciated by sports fans, who viewed him, especially in his early years of success, as sullen and self-contained, a hurdling automaton. Not until years later would he be viewed as a respected statesman.

Moses also made winning look so easy. "It just happens that my slow is faster than most athletes' fast," he said. "People either think that I'm a freak or that the other guys aren't any good."

Or, as pointed out by Leroy Walker, the U.S. Olympic track and field coach in 1976: "In an art gallery, do we stand around talking about Van Gogh? Extraordinary talent is obvious. We're in the rarefied presence of an immortal here. Edwin's a crowd unto himself."

He was born on Aug. 31, 1955 in Dayton, Ohio. With both his parents being educators, Moses took academics more seriously than most youngsters, though he also competed in sports. When his high school basketball coach cut him from the team and the football coach kicked him out for fighting, Moses turned to track and gymnastics. "I found that I enjoyed individual sports much more," he said. "Everything is cut and dry; nothing is arbitrary. It's just a matter of getting to the finish line first.

"Any individual sport is basically a gladiator sport. Back in the old days only one guy would walk out of the arena. In track, it's basically the same thing."

Rather than seeking an athletic scholarship, Moses accepted an academic scholarship to Morehouse College in Atlanta, majoring in physics and engineering. Though the school had a track team, it didn't have a track.

Mostly, Moses competed in the 110-meter high hurdles, 400 meters, and 4 x 100 relays. Just once before late March 1976 did he enter a 400-hurdles race. But once he started with the event, he made unbelievable advancement with his huge and economical 9-foot-9 stride and qualified for the Olympics.

As a 20-year-old, unknown scholar-athlete from a renowned black college, he burst upon the international scene at the Montreal Olympics. Not only did Moses win the gold medal in his first international meet, he set a world record of 47.64 seconds, breaking John Akii-Bua's mark of 47.82. His eight-meter victory over Mike Shine was the largest winning margin in the event in the Olympics.

"Edwin and I were ships passing in the night," Shine said.

Despite being the only American male track athlete to win an individual gold medal, Moses was not received with warmth by the public. Perhaps it was because of his serious expression, modified Afro, dark glasses and rawhide thong necklace.

He said that his major regret was that training for the Olympics had interfered with his studies, his grade-point average dipping to 3.57.

At Morehouse, where he basically coached himself, he was known as "Bionic Man" due to his improbable, fierce workouts. He took a scientific approach to analyzing his performance and developing his training methods. The method paid off in his breaking his own world record with a 47.45 at the Pepsi Invitational, an AAU meet, in 1977.

On Aug. 26, 1977 in Berlin, he lost to Harald Schmid, his fourth defeat in the 400 hurdles. What made this race so special is that this would be his last loss for almost a decade. The next week he began his amazing 107-finals winning streak (122 races overall) by beating Schmid by 15 meters in Dusseldorf.

"I have the killer instinct," Moses said. "It's ego. When I'm on the track, I want to beat everyone."

Moses, who received his B.S. from Morehouse in 1978, was prevented from winning his second Olympic gold medal when President Carter ordered the U.S. to boycott the Moscow Olympics in 1980. The 6-foot-2, 180-pound Moses had to settle for breaking his own world record again, running an incredible 47.13 on July 13 in Milan.

Also in 1980, Moses openly challenged the hypocrisy of the rules that prohibited amateurs from accepting money for competing and making endorsements. He believed that everything should be above-board rather than under-the-table.

While his fellow athletes appreciated Moses' stand on that issue, he didn't receive the same approval when he spoke out against steroid use, starting in 1983. He recognized the disastrous affects that rampant use of performance enhancing drugs by athletes could cast upon track.

"Somebody had to say something," he said. "What are these people doing to their bodies? Is winning worth that price? I don't think so."

After missing the 1982 season because of injury and illness, Moses came back the next year and had the race of his life. Shortly before a meet in Koblenz, West Germany, Moses dreamed he saw "8-31-83" and then, repeatedly, "47.03," which was a tenth of a second faster than his world record. On his 28th birthday, Moses raced to another world record, 47.02, a hundredth of a second faster than his dream.

Moses couldn't stop smiling. "Well, I haven't had a (personal record) for three years," he said with a laugh. The record stood until 1992.

|

At the 1984 Olympics, Moses became the second man to win two 400 hurdles. Getting off to a quick start, he won in 47.75 seconds.

Three years later, Danny Harris, who took the silver that day in Los Angeles as an 18-year-old, made sure the reign ended in Spain for Moses. On June 4, 1987, in Madrid, in their first head-to-head confrontation since the Olympics, Harris ran a 47.56 to beat Moses by .11 seconds.

After that defeat, Moses won 10 straight, including beating Harris at the 1987 World Championships in Rome. He leaned across the finish line in 47.46 to nip Harris and Schmid by about six inches.

But at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, though the 33-year-old Moses ran his fastest Olympic final (47.56), he finished third. The winner was teammate Andre Phillips, who had idolized Moses as a high school student and had lost to him more than 20 times, including at the Olympic Trials.

After retiring from track, the competitive Moses switched to bobsledding. In a late 1990 World Cup race at Winterburg, Germany, he and Brian Shimer took a bronze medal for two-man teams. Moses finished seventh at the 1991 World Championships.

In 1994, Moses received his Master's from Pepperdine and was elected into the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame. Since 1997 he has been president of the International Amateur Athletic Association.

When asked how he would like to be remembered, Moses answered, "Hopefully, as the guy nobody could beat. Maybe in the years to come, people will understand the things I have accomplished and realize, 'Wow, this guy was really something. Nobody's ever going to do that again.' "