By M.B. Roberts

Special to ESPN.com

If more is better, then Satchel Paige was the best.

He threw more pitches for more fans in more places for more seasons than anyone else did. Black or white. Then or now.

| |

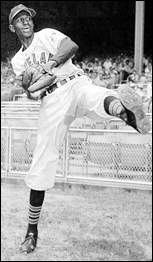

| Satchel Paige amazed barnstorming white major leaguers with his array of pitches. |

He threw mostly strikes. He was charismatic. And like the pink, drum-banging bunny who came along later, he just kept going and going and going.

Leroy "Satchel" Paige was the longtime Negro League star who eventually received his due in the majors. He reportedly got his nickname working as a baggage porter in Mobile, Ala., where he became a "satchel tree" by carrying several bags at once. "Satchel," the man, was literally ageless. (His birthdate, commonly reported as July 7, 1906, was never rock solidly confirmed).

Indisputable, though, is this: Paige reached the major leagues at an age when most pitchers have long stopped stressing their rotator cuffs. Also inarguable: the 6-foot-3, 180-pound right-hander is remembered as much for his witticisms as his extraordinary pitching talent and longevity.

He is perhaps best known for saying: "Don't look back. Something might be gaining on you." This gem was actually one of six "master maxims" which he had printed on his business card. Others sayings included: "Avoid fried meats, which angry up the blood" and "if your stomach disputes you, lie down and pacify it with cool thoughts."

He came to expect questions about his age. "Age is a question of mind over matter," he said. "If you don't mind, it doesn't matter."

Bill Veeck, legendary promoter and owner of the Cleveland Indians, concurred. In 1948, he signed Paige on the pitcher's 42nd birthday. Critics howled at the hiring of the oldest "rookie" in the history of the majors. The Sporting News accused Veeck of a "publicity stunt" and of demeaning" baseball.

Veeck responded: "If Satch were white, of course he would have been in the majors 25 years earlier and the question would not have been before the house."

The issue went beyond Paige's age: He was the American League's first African-American pitcher. Although Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier the year before, integration of baseball was still new.

Paige answered critics in his own fashion. He went 6-1 with one save and a 2.48 ERA and the Indians won the pennant by one game.

He also brought out the crowds. More than 200,000 came to see his first three starts, including a Cleveland record for a single game of 78,382.

Packing stadiums was nothing new to Paige. He was the hottest gate attraction in the Negro Leagues. During his entire career he performed before crowds estimated at 10 million in the U.S., Caribbean, and Central America, according to The New York Times Book of Sports Legends.

With Paige pitching, there was almost always a great show. He was known to wave his outfielders in to sit behind the pitcher's mound while he struck out a batter. He advertised promises that he would strike out the first nine batters.

Mostly, though, he pitched. Phenomenally. From his 1924 debut with the semipro Mobile Tigers to a sensational stint with the fabled Pittsburgh Crawfords to helping the Kansas City Monarchs win six pennants from 1939-48, his achievements were astounding. For example, he claimed to have started 29 games in one month for a white semipro team in North Dakota.

Pitching for the Crawfords (off and on) from 1932-37, Paige, according to one source, went 23-7 in 1932, then won 31 of 35 decisions in 1933, including 21 straight wins and 62 consecutive scoreless innings. Paige himself claimed to have won 104 of 105 games in 1934.

On off-days from the Crawfords, Paige sometimes freelanced. According to a 1953 Collier's magazine article, he wore his own solo uniform, with "Satchel" sewn across the front. His appearance, for a $500-$2000 fee, assured small-town teams a full house.

Paige also played during the off-season in Mexico, South America or the Caribbean. In one memorable stint he pitched for Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo's team in a series where the outcome, it was rumored, would decide an election. Heavily armed spectators watched from the first-base line.

Legend has it Paige arranged with police to escort him and his American teammates out of the country upon winning. It wasn't discussed what would have happened if they lost.

His barnstorming back home also had its share of thrills in exhibition games against white major leaguers. It was reported that Paige once struck out 22 of them in a game.

Joe DiMaggio called him "the best I've ever faced, and the fastest."

In 1934 and 1935, Paige opposed baseball's best pitcher, Dizzy Dean, in six exhibition games, winning four.

"My fastball looks like a change of pace alongside that pistol bullet old Satch shoots up to the plate," Dean said. "If Satch and I were pitching on the same team, we'd clinch the pennant by the fourth of July and go fishing until World Series time."

Dean and other major league challengers, such as Bob Feller's All-Stars, were dazzled by Paige's bag of pitches, each complete with its own nickname: bee ball, jump ball, trouble ball, the two-hump blooper and Long Tom. His most famous delivery was the hesitation pitch, which he developed in the 1940s and threw after deliberately pausing as his left foot hit the ground.

Paige was the sixth of 12 children born to John Paige, a gardener, and Lula Coleman, a domestic worker in Mobile. He went from being a satchel-toting boy, to a rock-throwing teenager. In reform school, where he was sent for truancy and shoplifting, the rock-thrower switched from rocks to baseballs.

|

|

| Previous poll results |

As the star of the Negro Leagues, he made more money than any other African-American player of his time, as much as $40,000 a year. He traveled the world and the country more times than he could count. For a while he even had a plane for his Satchel Paige All-Stars.

Finally, he was invited to play in the majors. It hurt him when Robinson was selected to be the first African-American to play this century, he said in his 1967 autobiography, "Maybe I'll Pitch Forever."

But he didn't get bitter. Not as long as his arm still worked. After pitching two seasons for the Indians, he pitched three years for the St. Louis Browns as a spot starter and reliever, compiling a 12-10 record in 1952.

On Sept. 25, 1965, he became the oldest to pitch in the major leagues. Ever the showman, the 59-year-old Paige sat in a rocking chair in the bullpen while a nurse rubbed liniment on his arm. Then he threw scoreless three innings for the Kansas City Athletics against the Boston Red Sox, allowing only one hit, a double by Carl Yastrzemski.

For his major-league career, his record was 28-31 with a 3.29 ERA and 32 saves.

Paige barnstormed virtually nonstop into his 60s. His final appearance in a major-league uniform came in 1969 when he was a coach for the Atlanta Braves.

In 1971, Paige was the first of the Negro League stars to be elected into the Hall of Fame.

He died of emphysema at 75 on June 8, 1982, in Kansas City. Paige's impact on baseball will last even longer than he did. He blazed a wide trail for generations of African-American players during every slow stroll out to the mound. He never ran. Never jangled.

He was the ageless Satchel Paige.