By Ron Flatter

Special to ESPN.com

Didn't we hear about Jim Thorpe from our dad or granddad?

We certainly never saw him in person. But we sure knew the legend. He was the Olympic track champion who lost his gold medals because he played minor league baseball. Long before Bo and Deion, he was the athlete who played pro baseball and football at the same time.

| |

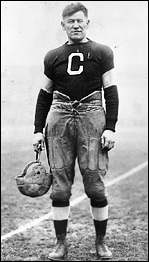

| Jim Thorpe was an all-American in college as a four-position player. |

He was voted "The Greatest Athlete of the First Half of the Century" by the Associated Press and became a charter member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. But Thorpe's legend was galvanized into America's conscience at the 1912 Olympics.

He won the decathlon and pentathlon in Stockholm. When King Gustav V of Sweden congratulated Thorpe, he said, "Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world."

Thorpe reputedly replied, "Thanks, king."

He returned home a star. Thorpe's name was so big, he received that most American of honors -- a ticker-tape parade in New York City. "I heard people yelling my name," he said, "and I couldn't realize how one fellow could have so many friends."

Later that year, Thorpe scored 25 touchdowns and 198 points to lead an outstanding Carlisle Indian School team. That launched him toward a pro football career, highlighted in 1920 when he helped found the American Professional Football Association, which would evolve into the National Football League.

That was the flash point for a turn in Thorpe's life. Although he would continue to write his legacy as an athlete nonpareil, he was stripped of his gold medals in 1913 after it was discovered he had violated amateur rules by being paid to play minor league baseball in 1909 and 1910. Attempts to have the medals returned were not rewarded until 1982, almost 30 years after Thorpe's death.

He was born on May 28, 1888 near Prague, Okla., on Sac-and-Fox Indian land. His given name was Wa-Tho-Huk, which means "Bright Path."

Thorpe was one of the few in his immediate family to have a long life. His twin brother Charles died of pneumonia at age 8. Both his parents died when he was a teenager.

As a child, the rambunctious Thorpe became his athletic father's protege, at times running 20 miles home from school. "I never was content," he said, "unless I was trying my skill in some game against my fellow playmates or testing my endurance and wits against some member of the animal kingdom."

Although he showed immediate promise, Thorpe was only a star in his schoolyards. That changed in the spring of 1907. Attending Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, Thorpe was clad in work clothes when he walked past track practice one day. He watched as others failed to clear a high-jump bar set at 5-9. Thorpe gave it a shot and, despite wearing heavy overalls, he cleared the bar easily.

Two years later, the 5-foot-9 1/2-inch, 144-pound Thorpe almost single-handedly overcame the entire Lafayette track team at a meet in Easton, Pa., winning six events.

"After it was all over, Thorpe couldn't tell you how he did it," Lafayette coach Harold Anson Bruce said. "Everything came natural."

During the summers of 1909 and 1910, Thorpe was paid - reports have him earning from $2 a game to $35 a week - for playing for Rocky Mountain in Fayetteville in the Class D Eastern Carolina League. He naively used his real name, unlike other collegians who adopted pseudonyms to foil amateur rules.

Then again, Thorpe may have thought he would never compete as an amateur again. It took some arm-twisting by coach Pop Warner to get Thorpe to come back to Carlisle for the 1911 football season.

Warner promoted Thorpe as "the greatest all-around athlete in the world." Thorpe dominated an 18-15 upset of highly regarded Harvard with his four field goals and outstanding running in front of 30,000 in Cambridge. It was the highlight of a season in which Thorpe, halfback/defender/punter/place-kicker, was named an All-American.

Then came that grand summer of 1912. On July 7, he won the Olympic pentathlon. The next day, he finished tied for fourth in the high jump and on July 13, he came in seventh in the long jump. Then came the decathlon, and Thorpe set a world record with 8,412 points. The standard Thorpe set was so high that, if he had duplicated his marks 36 years later, they would have held up well enough to win a silver medal.

After collecting Olympic gold and New York ticker tape, Thorpe picked up where he left off for Warner's Carlisle football team. He ran spectacularly in a 27-6 Army win. In a Thanksgiving snowstorm, Thorpe had three touchdowns and two field goals in a 32-0 victory over Brown. He was named an All-American again.

Two months later, Worcester (Mass.) Telegram writer Roy Johnson discovered Thorpe's pay-for-play past. Asked for his response by the Amateur Athletic Union, Thorpe wrote, "I hope I will be partly excused by the fact that I was simply an Indian schoolboy and did not know all about such things. I was not very wise in the ways of the world and did not realize this was wrong."

In January 1913, Thorpe was stripped of his amateur status and, with it, his two Olympic gold medals. After leaving Carlisle, Thorpe signed to play baseball and be a gate attraction for the New York Giants. He admitted he was more "a sitting hen, not a ballplayer."

Troubled by the curveball, Thorpe hit only .252 in his six seasons (1913-15, 1917-19) as an outfielder with the Giants, Cincinnati Reds and Boston Braves. His best season was his last one, when he batted .327 in 60 games for Boston.

|

In 1915, Thorpe played two football games for the Canton Bulldogs for a pricey $250 per contest. He decided to stay on as the biggest drawing card for a team that would be recognized as "world champion" in 1916, 1917 and 1919.

While playing for the Bulldogs in 1920, Thorpe was named the first president of the American Professional Football Association. After playing with Cleveland in 1921, Thorpe created and played for the all-Native American Oorang Indians. Stints with Rock Island, the New York Giants and a return engagement with Canton followed through 1926.

After more than a year out of football, Thorpe signed with the Chicago Cardinals to make one last appearance against the Chicago Bears on Nov. 30, 1928. "Jim Thorpe played a few minutes but was unable to get anywhere," one reporter wrote. "In his forties and muscle-bound, Thorpe was a mere shadow of his former self."

Thorpe's days as a competitive athlete were over.

Without sports, Thorpe drifted. His drinking, an issue before, became destructive. There were many fights, and almost as many jobs. He took odd jobs under assumed names, working as a painter, ditch digger, deck hand, auto-plant guard and bar bouncer. The fifties brought him renewed fame. Besides being named top athlete of the half-century, he was portrayed by Burt Lancaster in the 1951 film "Jim Thorpe All-American."

Thorpe died at 64 of a heart attack on Mar. 28, 1953. By then, he was living in a trailer in Lomita, Cal. In 1954, his body was moved to Mauch Chunk, Pa., a small town which agreed to change its name to Jim Thorpe.

Pleas to have Thorpe's good name restored to Olympic rolls persisted. They were based on a rule, in effect in 1912, which said officials had 30 days to contest an athlete's amateur status. Thorpe's standing did not come into question until six months after the Games.

It was not until Oct. 13, 1982, that the International Olympic Committee finally agreed to restore Thorpe's gold medals. The following January, replicas were presented to Thorpe's family.