|

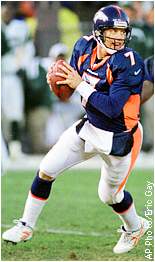

Monday, Feb. 1 12:05am ET Elway's legacy larger than life |

||||

There isn't much left to say about John Elway, except for the mostly unexamined Vampire Years.

Ha! Made you look.

Therein lies the conundrum that is reassembling the life that is John Elway's. Part arm, part hair, part teeth, part pigeon-toed gait. Part baseball player, part golfer, part car dealer. Part Stanford icon, part Denver icon, part Baltimore kick-me doll. A man who knows his place in history, the length of his shadow, the breadth of his wingspan, the value of his stock portfolio, the whereabouts of his kids and the contents of the caption beneath his bust in the Hall of Fame.

And of course, we know it, too. Only a few athletes in the modern American jockocracy have been more analyzed, psychoanalyzed, metabolized, digested, reinvented and dressed for success as Elway. Muhammad Ali, surely. Michael Jordan, indubitably. O.J. Simpson, most assuredly, although not in your normal ways.

Then comes Elway. A rare man whose legacy was actually determined before he stopped playing. A man who still has half his life left to live, but whose place in history has already been established.

Why, the whole thing would be kind of sad, except for the happy marriage, the fulfilling family, the fabulous wealth and the low golf handicap. Frankly, the only way he could screw this up now is to enter politics, and there is nothing in Elway's past that suggests he could lose his mind in such a comprehensive way.

In short, he looks sensational now, on the verge what many people expect will be his final game. The reason he looks this good, though, is the way he got here. He seemed like the man with the golden life, smacked into a series of walls that would have cracked less self-possessed men, and came out on the other side all the bigger, better and criticism-proof.

For example, he is considered by most right-thinking people to be the best quarterback Stanford ever produced, and Stanford has produced plenty of them. Yet, none of his three teams ever reached a bowl game, and he lost more games than he won. Weirder yet, his last game was the one California won by running a kickoff back through the Stanford band, a play he still says all but ruined his college career by itself.

He was drafted by Baltimore despite his warnings the Colts would never see him alive, decided to sign with the New York Yankees to press his point, and was traded to Denver for what turned out to be the good of the NFL.

He was immediately elevated to emperor of Denver, a growing town that in the early '80s was still gripped by an inferiority complex so huge that you could brush Godzilla's teeth with it. When he got the Broncos to the Super Bowl in his fourth full year, he was bigger than big, but the Horsies were soundly whipped by the New York Parcells, and then again the next year by Washington, and two years after that by San Francisco.

At this point, he achieved what his current tight end Shannon Sharpe would consider a deserved reputation as a loser. A majority of sentient Denverites, having watched four Super losses by an average score of 41-12, asked their heroes never to reach the Super Bowl again, and Elway was criticized for all that, plus his choice in Halloween candy. He wondered if it was all worth it, and we all agreed he probably had a point.

He stuck it out, though, only to embroil himself in a well-publicized spitting contest with former coach Dan Reeves over the direction and focus of the offense. Though the majority of fans supported him, he did take his share of abuse for trying to name his own coach (and essentially succeeding).

We mention these setbacks only as contrast to what has been by any measuring stick a superb career, and because as his career ground toward its end, he became a figure of national sympathy. "When Will John Get His Ring?" became not only Denver's leading hysteria but a national talking point. He became a figure of sympathy, and when the Broncos finally hit the lotto last January, he became a figure of perseverance.

See, Americans are always mistrustful of the person who gets it all too soon. They want to see adversity. They want to see suffering, and then they want the hero to get the girl in the end. If we didn't feel that way, every domestic movie ever made would be seven minutes long.

John Elway looked like he would have it all by the time he was 14, but he didn't actually get it all until he was 37. As struggles go, it was hardly the stuff of a Steinbeck novel, but at least as he stands atop his own personal mountain, he does so with a little dirt on his hands and knees. That is the Elway legacy.

As for the Vampire Years ... well, that's a story for after he retires.

Ray Ratto of the San Francisco Examiner is a regular contributor to ESPN.com.

|

| Copyright 1995-98 ESPN/Starwave Partners d/b/a ESPN Internet Ventures. All rights reserved. Do not duplicate or redistribute in any form. ESPN.com Privacy Policy (Updated 01/08/98). Use of this site signifies your agreement to the Terms of Service (Updated 01/12/98). |