|

Saturday, Jan. 16 4:29am ET The Mastermind vs. The Tuna |

||

|

By Lynn DeBruin, Scripps Howard News Service

DENVER -- They built their reputations on different coasts, on different sides of the line of scrimmage, in different decades.

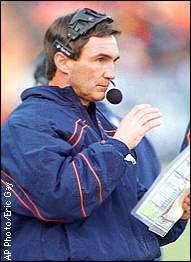

On the sideline they remain a study in contrasts. One, dwarfed by players around him, is usually focused and composed, an intense stare his most prominent feature. The other, with his linebacker's physique, won't think twice about ranting to make his point.

What's remarkably similar about Mike Shanahan and Bill Parcells, however, is their ability to motivate, win and inspire loyalty.

On Sunday, for only the third time as head coaches, their paths will collide when the Denver Broncos face the New York Jets at Mile High Stadium in the AFC Championship Game.

"Why do they believe in him? He wins. It's not hard to understand," said George Young, who was general manager of the New

York Giants when Parcells won his two Super Bowl rings. "If they feel they can win with a coach, he has great credibility."

In Shanahan's case, his straightforward, businesslike approach is important.

"There's no question you generate loyalty, any coach on any level will, if you treat your players right and they feel they're being

treated right and respected," Broncos kickoff returner Vaughn Hebron said.

Translation: Shanahan tells players what he expects from them, then provides them with the capabilities to meet the challenge. If they can't, they're gone. Players view it more or less as a pact, one that comes with some perks.

"Guys respond to him because he does the little things that add up a lot to players during the course of a long season," guard David Diaz-Infante said. "Like getting your own room on the road or having that extra day off if you win, not beating you up mentally or physically.

"Guys are willing to play here. Guys are willing to sign those long-term contracts."

That both coaches have proved they can win doesn't hurt.

Shanahan, 46, boasts a 5-1 record in the playoffs as a head coach; Parcells, 57, has gone 11-5.

"Winning certainly helps," said Broncos backup quarterback Bubby Brister, who saw the other side with the Jets before Parcells arrived in 1997.

"But with Mike, he's a good judge of character. He's done a great job of bringing in players who fit . . . who care about each other and want to play for each other and him."

Both Shanahan and Parcells are sticklers for preparation and offseason workouts and maniacal about control, demanding power in

personnel decisions.

Shanahan, the Mastermind, monitors every detail, scripting everything from the first 15 plays in a game to the first 10 speeches

of training camp.

Parcells, the Tuna, does not allow his assistant coaches to talk to the media. His practices, except for training camp, are closed to the press. Inside those off-limit areas, Parcells is widely known as a needler, a guy who knows which buttons to push.

Early this season, then-starting quarterback Glenn Foley kept insisting he was recovered from a rib injury. Parcells didn't believe

him. One day Parcells came up behind Foley in practice and gave a good

squeeze. Foley doubled over in pain.

When wide receiver Wayne Chrebet said he was over an ankle injury,

Parcells provided a little kick to check for himself.

When the Jets prepared to play AFC East foe Miami, Parcells made sure former Dolphins linebacker Bryan Cox was ready. He left a

half-empty gasoline canister in Cox's locker, a not-so-veiled suggestion that Cox had nothing left in the tank.

"Nothing surprised me about Bill," said Young, now an executive

in the NFL office.

Even players who thought they knew him well have been caught off-guard at times. That happened in October when Parcells, still

seething over a loss to lowly St. Louis, walked off the practice field after becoming furious with the effort.

Not that Parcells doesn't know when to praise and stroke his players.

"The best teachers are also the best actors . . . The guy is a Hall of Fame coach," Young said of Parcells. "As for Shanahan, give

him a little time. He's made a wonderful impact, but let him run a little."

When it comes to differences, nothing further separates the two than their view of Raiders owner Al Davis.

To Parcells, Davis is a confidant, a man who provided invaluable advice when Parcells faced his toughest season ever in 1983.

To Shanahan, Davis is the enemy, a man for whom he won't hide his disdain over getting his walking papers as head coach of the L.A. Raiders in 1989.

But their desire to win remains the biggest common denominator.

Parcells, in his 1995 book Finding a Way to Win, contemplated why he puts up with the stressful life.

He described the wildly stimulating, euphoric sensation of victory. Yet he admitted the rush of reaching the pinnacle -- winning a Super Bowl -- is short-lived because it creates an insatiable desire to win it again.

Bob Knight, who coached basketball at Army when Parcells coached the football team, told Parcells he would want a second championship even more than the first.

"I found out he was right and that it only gets worse. Because after I won the second one, I really wanted to win a third," Parcells

wrote.

Parcells got his chance two years ago with the New England Patriots, only to lose to Green Bay in Super Bowl XXXI.

Shanahan beat Green Bay last year to win his second Super Bowl, adding to the ring collection he started as offensive coordinator of the Super Bowl XXIX-champion San Francisco 49ers.

Parcells still wants that third ring. He didn't hide that fact after leading the Jets to their first AFC East title. The following

week he showed up for a team meeting wearing his Super Bowl XXV ring He didn't say a word about it, but his players couldn't help but notice the sparkle of diamonds.

The motivation was clear.

When his 1990 Giants won Parcells that ring, they were an overachieving team, with an unlikely quarterback (Jeff Hostetler).

They won their first playoff game at home, then had to go on the road against the defending champions and their Hall of Fame

quarterback (Joe Montana). They ended up beating San Francisco, then

went on to beat Buffalo and its high-powered offense.

The parallels to 1998 are unmistakable.

Lynn DeBruin writes for the Rocky Mountain News.

|

| Copyright 1995-98 ESPN/Starwave Partners d/b/a ESPN Internet Ventures. All rights reserved. Do not duplicate or redistribute in any form. ESPN.com Privacy Policy (Updated 01/08/98). Use of this site signifies your agreement to the Terms of Service (Updated 01/12/98). |

AFC: Tuna stocks the cupboard

AFC: Tuna stocks the cupboard